The Black Phone feels like a hodgepodge of Stephen King’s greatest hits

Ethan Hawke reunites with director Scott Derrickson and his Sinister co-writer C. Robert Cargill for child kidnapping horror The Black Phone. Despite some chilling moments and Hawke’s deeply disturbing performance, Katie Parker found it to be a mixed bag.

The Black Phone

If you, like me, are a fan of horror films, the chances are you’ve seen quite a few movies about people being kept in basements. From home-invasion horror Don’t Breathe, to M.Night Shyamalan’s Split, to sci-fi spin-off 10 Cloverfield Lane, to dark cannibal comedy Fresh, I’ve spent what feels like a significant amount of my movie-watching life observing the plight of characters chained to the walls of grotty below ground living quarters.

Now, what is basically a veritable sub-genre has a new entry: stranger danger horror The Black Phone.

Adapted from the short story by Joe Hill (who just casually happens to be the son of literary horror maestro Stephen King) The Black Phone sees Sinister collaborators Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill reunite with Ethan Hawke for another bout of suburban chills—this time with Hawke as the villain.

Set in a small Denver town in the 1970s, The Black Phone invites us into a community beset with the hysteria of stranger danger. Boys in the town have been disappearing—and wherever they’re going, they’re not coming back.

With police still unable to pinpoint the who/what/where of the culprit known colloquially as ‘The Grabber’, no one knows where the boys are being taken—and from the moment The Black Phone introduces us to sweet, shy local boy Finney (Mason Thames), it’s clear he’s going to find out.

Small, gangly, and under siege from the school bullies, Finney’s home life is barely better than his school life. Living in quiet, cautious fear of his abusive, alcoholic widower father (Jeremy Davies) and his mysteriously prophetic sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), Finney grows increasingly unnerved as boys he knows vanish off the face of the earth—until one day he too meets The Grabber, and finds himself imprisoned in a subterranean basement furnished with little more than a grubby toilet and an old, disconnected wall-mounted black telephone.

But just as Finney thinks he has met his maker, he realises something has gone wrong in his captor’s plan—and with The Grabber seemingly detained upstairs, Finney inexplicably starts to hear the disconnected phone ringing, and a supernatural force arrives to help him break free.

As far as chills go, The Black Phone is a bit of a mixed bag. Tonally confused—Finney’s sister and her psychic gifts are the source of both the film’s most upsetting scenes of child abuse and the comic relief—its occasional jump scares feel half-hearted and hollow, and ultimately undermine moments that would have been far more unsettling without the theatrics.

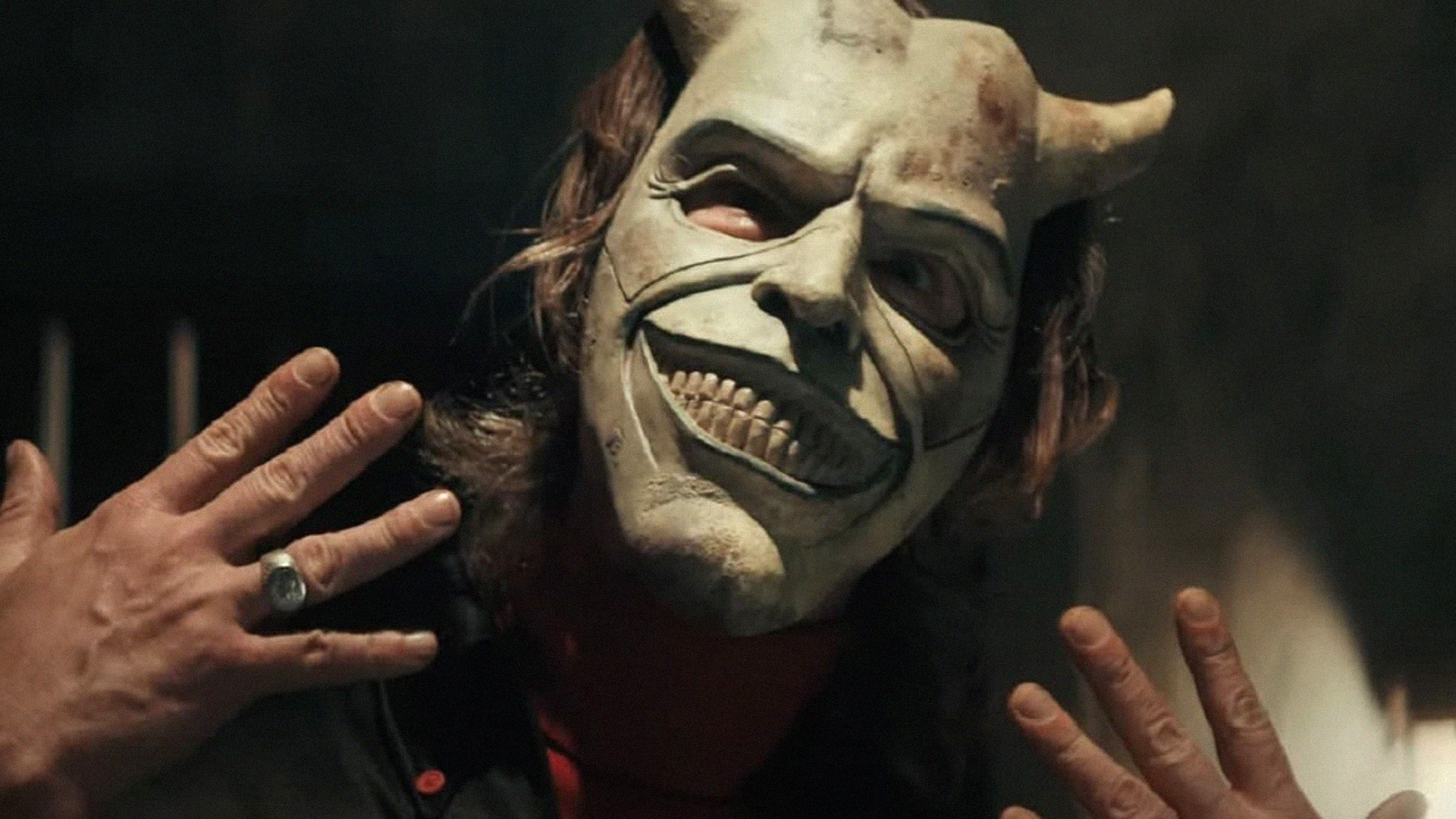

Thankfully, Derrickson and Cargill have an ace up their sleeve: Hawke’s strange, sad, and deeply disturbing performance as The Grabber.

A magician by trade (or at least that’s what he tells Finney) he remains as enigmatic and disturbing a presence as Hill originally drew him, delivering lines lifted more or less verbatim from the story.

Clad in his creepy, customisable mask—we never see Hawke’s entire face—and speaking in a weird, high, sing-songy voice, it soon becomes apparent that he is relying more on his victim’s vulnerability than any actual predatory prowess to carry out his plan. As pitiful as he is repulsive, Hawke’s performance paints a chilling portrait of mundane menace, all the more horrific for that fact that he is far from a criminal mastermind.

At just 30 pages, the short story on which The Black Phone is based is not a long one. Quick, concise and satisfying brutal, Derrickson and Cargill’s screenplay seems determined to flesh it out—and even at the relatively brief runtime of 103 minutes, the embellishments to Finney’s backstory start to stretch a little thin.

The psychic sister, the vicious school bullies, the abusive father, all are additions to the story and unmistakably reminiscent of none other than papa King himself. Invoked spiritually and aesthetically again and again, in ways that feel increasingly trite and disappointingly cynical, there are times when The Black Phone feels like a hodgepodge of King’s greatest hits.

It’s a shame—the things that made Hill’s short story so disarming are still there, and as abduction horrors go Derrickson and Cargill hammer home the grim nastiness of the genre. Sadly diluted with ghostly apparitions and subplots about being cool at school, however, The Black Phone indulges in too many Hollywood tropes and cheap tricks to turn its subject matter into anything truly special.