Despite another magnetic Gandolfini performance, The Many Saints of Newark feels mostly irrelevant

The Sopranos prequel has huge shoes to fill, turning back the clock to Uncle Dickie’s Jersey reign. Luke Buckmaster writes that The Many Saints of Newark is a lightweight gangster story that’s been told better before.

The Many Saints of Newark

It’s an irresistible premise, at least for fans of David Chase’s supremely good gangster series: The Sopranos as a period piece, swapping turn of the century settings for the late 1960s. The people this film portrays are not the kind who gathered on the mud at Woodstock in hippy shirts and granny glasses, taking acid and singing songs about love and peace.

These dudes are wiseguys from the Italian mafia, interpreting ‘liberty and pursuit of happiness’ as a die-by-the-sword, eye-for-an-eye way ideal, punctuated by rackets, murders and making various offers people can’t refuse.

Instead of The Many Saints of Newark bringing us up to date with what a Sopranos-esque world might look like in the current cultural moment, which would be a difficult but potentially fascinating exercise, this nostalgia-imbued spin-off movie goes the other way—back to a more hospitable era for gangsters. Sadly it has the vibes of a lightweight Scorsese knockoff: not terribly made but filled with settings and circumstances explored, to far better effect, many times before.

Scorsese is a tough benchmark, but then again so is The Sopranos. One of the front-running titles in the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of television (a term coined in a era when there were far fewer pedigree programs than today), the show was most famous for James Gandolfini’s portrayal of affably evil New Jersey mobster Tony Soprano, attempting to fend off a mid-life crisis symbolised by the arrival of a family of ducks in his swimming pool.

The Many Saints of Newark is bookended by stylistic flourishes that will pique the interest of fans of the show, though it rarely offers a strong connection to the critically acclaimed and popularly appreciated series. The film begins with a shot crawling across the ground at a cemetery, the camera’s presence activating various voices from the grave before arriving at the tombstone of Christopher Moltisanti—Tony’s late nephew and protégé, who narrates Newark posthumously.

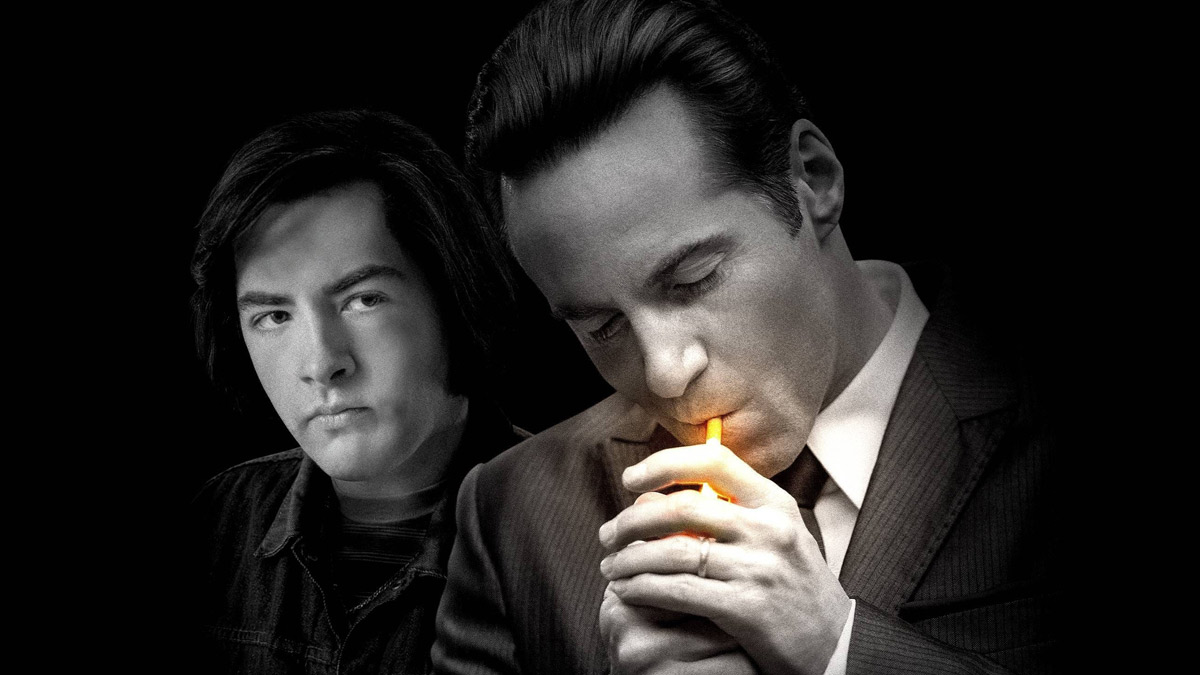

The ace up director Alan Taylor’s sleeve is a magnetic performance from Michael Gandolfini as a young Soprano—who is a wise guy but (for now) not in the mafia sense. His acts of proto-gangsterism include (and I would have loved to have seen more of these) stealing an ice cream truck and taking it for a spin, handing out freebies to local kids.

My first inkling was to describe the actor’s likeness to James Gandolfini as ‘uncanny’ or words to that effect, though the opposite is true, given Michael is the late actor’s son. Sameness is in his blood; in his bones. Mother Nature herself played a role in this sensational twist of casting: creating a human, genetic special effect more impressive than what current era CGI whizbangery can achieve (for a case in point consult The Irishman, in which de-ageing technology turned Robert De Niro’s face into a weird, shapeshifting form, sort of real and sort of not).

What a downer, then, that 50 minutes of running time elapses before The Many Saints of Newark wheels out its greatest asset and son-of-Gandolfini appears on screen. By this point it’s clear the story is not predominantly his. It is rather—as the key art puts it—the tale of the man ‘WHO MADE TONY SOPRANO’, referring to his father-like mentor Dickie. Despite a decent, thoroughly believable, well-judged performance from Alessandro Nivola, Dickie has the personality of a henchman rather than a protagonist: a bloke who does some dirty work and raises his voice from time to time but doesn’t stick out from the pack.

Among the screenwriters’ more interesting decisions is to integrate into the dramatic context the Newark race riots of 1967, an event sparked by police brutality. At first blush this seems to connect in essence to the Black Lives Matter movement, but it’s unclear what the filmmakers are getting at; they stop short of suggesting Tony Soprano was motivated by distrust of authorities. The historical setting leads to a compelling albeit empty image: the sight of young Tony looking out his bedroom window, the smoke and fire of rebellion clogging the sky outside in an eerie orange.

Why didn’t they make more of Michael Gandolfini and centre the film around him? The Many Saints of Newark could have mythologised Tony Soprano’s young life, proposing all sorts of connections to the man he became. Instead the production as a whole feels digressive and mostly irrelevant—even for the superfans. The Breaking Bad spinoff El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie is better, edgier, and more interesting, but like Newark it cannot replicate, in the far tighter movie format, anything close to the tense and addictive magic of its TV origins.