Interview: ‘Calvary’ director John Michael McDonagh

Calvary is writer-director John Michael McDonagh’s excellent follow-up to The Guard that “manages to provoke both thought and laughter, while saying something profound about the human soul.”

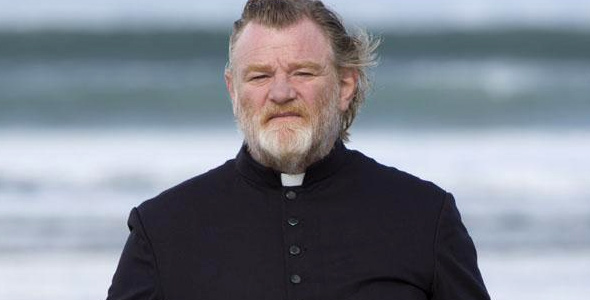

Brendan Gleeson plays a good-natured Irish Catholic priest who, while trying to believe the best of his parishioners, is continually shocked by the spiteful and confrontational inhabitants of his small country town. Dark thoughts begin to take over when his life is threatened during confession.

It’s one of the best films of the year so far (as Matt Glasby’s 5-star review will attest), and is currently playing in cinemas nationwide. Click here for movie times.

Giles Hardie had a great yarn with McDonagh about the film.

HARDIE: So, where did the idea for ‘Calvary’ come from?

MCDONAGH: We were just finishing up on location on The Guard, which was in County Galway. So we had a lock-in, in a pub, in this little town. Myself, Brendan Gleeson and the crew – Don Cheadle was there, drinking his Guinness.

It got quite late and Brendan said what are you planning on doing next? I had no plan. I said, ‘you know I bet there’s going to be lots of movies made about the scandals in the church. They’ll all be worthy and self-serving and right on.’

I said, ‘we should make the opposite of that, where the lead character is a good priest, not a bad one, just to flip it on its head.’

Apparently he had had a mentor at school, who had really helped him creatively, and he said ‘I always wanted to play a character like that.’

Most movies don’t follow good people. They follow conflicted people or an anti-hero. It’s usually the villain in a movie that drives the movie on. But purely someone who’s good is quite rare, when you look at a movie these days.

So I thought, that’s an interesting narrative challenge, I’ll do that. So the idea eventually became: We’ll have a good man and everyone around him is bad.

That was the over-arching view of it. From the initial instance it was going to be he basically suffers for the sins of humanity, I suppose, or the sins of the church.

A good priest surrounded by awful people allows you to tackle more issues than just the church sex abuse scandal that is the starting point.

It’s like you’re taking those archetypes – like the rich man in the village – and you go, where did he get his money from? Of course, he ripped people off during the financial scandals.

Then you want to make it a bit deeper than that. That character, played by Dylan Moran, is one of the richest in the film. By the end he is the only person who really asks for help. He’s not as one-dimensional as he first appears. That was quite an enjoyable character to write.

Then you got of course: An atheistic doctor; the barman in the local pub.

And then you go: What are the priest’s daily rounds?

They go to visit the sick, the lonely. They deliver the last rites to somebody. That gives you the idea for a scene. And gradually you build up these scenes and it becomes a framework.

And then you still have the backbone of the thriller aspect of somebody is going to kill him, or attempt to kill him, or says they are, by the end of the movie.

When you start with a promise to kill your hero at the end, is it a challenge to make the finale a shock?

What happens, if the movie works, is that you have the big set up in the first scene where his life is threatened, but gradually you start to forget about it and it only comes back in moments.

Once you get into the last half hour, if the film works, you gradually go ‘oh god it’s going to happen. Or will he try to flee? Will he try to escape?’

Forgive the pun, but was the end preordained from the first time you came up with the idea?

I knew whether he would die. But I was about two thirds of the way through before I decided which person was going to be the threat.

It’s an amazing ensemble cast. It seems like you cherry picked the best talent in Ireland. You even cast Brendan’s son Domnal as a convicted killer he visits in prison.

I was a little worried by that to start with. I thought it would take the audience out of the scene if they start saying, ‘oh that’s Brendan and that’s his son’. So we gave him that kind of odd bowl haircut and stuff to take that away. Maybe they might not recognise him.

Then we’ve got Aiden Gillen, who I guess is well known for Game of Thrones, but I don’t really watch it. I’d done a short film with him years ago. I know him personally.

And there’s Chris O’Dowd of course. There was a point when the character that Chris O’Dowd plays, I hadn’t cast it yet, and we were at an awards ceremony. Chris O’Dowd was the host and he was very anarchic and acerbic and he was drinking throughout the show. As the show went on he became even more sarcastic. Myself and my wife looked at each other and thought ‘oh my god it could be him to play that part’, which we hadn’t thought of. And during that show he was making jokes about why wasn’t he seen for The Guard because he’s a great comic actor.

We walked out going ‘if he’s saying that he’d probably do this.’ So we sent him the script and the next day he came back interested in doing it and the next day we met in a pub and he said yes.

A lot of the actors, they’re more known for comedy. I find it quite enjoyable casting those people, because on a pragmatic level they’re very good fun on set. They make the filmmaking enjoyable a lot of those comic actors.

Plus they fell that they’re underrated in a way because they do comedy not drama. Which is silly because comedy is just as difficult as drama is. Once they’re given a chance they’re very focused and up for doing it.

The guy who plays the barman, Pat Shortt, is one of the biggest comedy stars in Ireland, has hit sitcoms and that. The guy who plays the priest David McSavage does a really hard hitting satirical show. They’re all there and they’re all good fun.

And of course Dylan Moran is pretty well known.

You fill your frames with a lot of detail. Are you a bit like Wes Anderson, meticulously planning every detail?

It’s funny you say that. I am quite OCD about framing and stuff like that and I am a big fan of Wes Anderson, but I don’t think I take it as precisely. I still leave a bit of room for a bit of messiness.

Every now and again for a special scene, I will frame carefully. The actors joke about me moving about the set and moving stuff a half-inch and stuff like that. That’s the good thing about those monitors. You can check everything in the image. If you are a bit OCD, you can endlessly reframe. Eventually though you’ve got to shoot the scene.

I do storyboard everything as well. Ideally I try to get the precision that a Wes Anderson has, but with the messiness of real emotional acting as well.

And you put extra story in the frame, are there Easter eggs throughout the film?

I do put things in backgrounds quite a lot. In The Guard there’s this scene where Don Cheadle’s leaving, and he says goodbye to Brendan’s character. And he’s got this carry-on case and you can glimpse these two toy sharks on top of the case. Early on in the movie the three villains are seen at an underwater aquarium and those little sharks were on sale there and I thought I’ll put them on Don’s bag because it implies he was there at the same time they were and didn’t even notice the villains wandering around.

In Calvary the Inspector is showing his gun and he says, I killed a man with it once in the Wicklow Mountains. The priest says, which case was that? He says, he was just pissing me off. Later on Veronica comes out of the water and talks about her father who was accidentally shot in a hunting accident. My thing is, the inspector killed him.

There’s lots of that stuff in the background of films. It’s whether people see them or not, it’s up to them.

So you’re toying with us.

Yes.

Was there any temptation to get Don Cheadle in this?

No. But I am the type of director that if he was visiting Ireland when we were shooting I would say Don would you come down and be in the background of this scene? Because it would be funny.

The Inspector, he’s been in both films. In The Guard he gets away with the pay-off money. No one seems to realise that. They never get caught. Now he’s in County Sligo with his rent boy. When I do the third part of the trilogy, that character is going to come back for his final apotheosis. Let’s put it that way. He’s going to be in it. He’ll be in the end.

The trilogy?

There will be a third one. It’s going to be about a spectacularly abusive paraplegic, Brendan Gleeson, rattling around south London in a wheelchair trying to solve the murder of one of his friends. So that will have a thriller framework but have a lot of very dark comedy all the way through.

Given your style of visual obsession are you equally controlling of the script?

I am controlling about the script. Casting comic actors, it’s fine if they riff on a line or if they improvise. But as I usually say to them, it’s unlikely that you’re going to come up with a better line than I’ve written anyway.

Let’s face it. I will have had the script for 6-8 months before we got into pre-production. I’ve thought about it quite a lot. You, the actor, have only arrived on set that day, you might have only been going through it for a couple of weeks.

Someone like Chris O’Dowd will play around with the rhythms of a line more than rewriting or improvising. He’ll just deliver it differently to how I imagined. Sometimes it’s better. Sometimes it’s not. As long as it comes back to the meaning of the scene.

There will always be a line you want said exactly as it’s written and others they can play around with and it’s fine. Don Cheadle on The Guard would say ‘An American wouldn’t say it the way you’ve written it. Do you mind if I say it this way?’ I’d reply, ‘No, that makes it more authentic.’

Careful framing, script adhesion. You’re not painting a portrait of a director who has fun on set. No wonder you want comedians!

And I want to cast actors who like a drink as well so on Friday night we can all got out and get hammered basically.

I don’t find writing enjoyable either. It’s very boring sitting alone in your room for three to four hours a day.

The shooting, sometimes it can be enjoyable, but basically what you’re trying to do is impossible. In your head it’s perfect. And when you’re shooting you’re trying to approximate as much as you can the perfect movie you’ve got in your mind. You’re never going to make that perfect movie. So you just have to try and do the best that you can. You know on a low budget movie there’s all these things going on. A camera may break and you can’t get the shot you want and you have to move on.