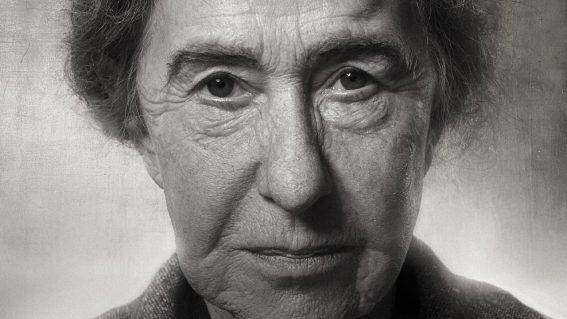

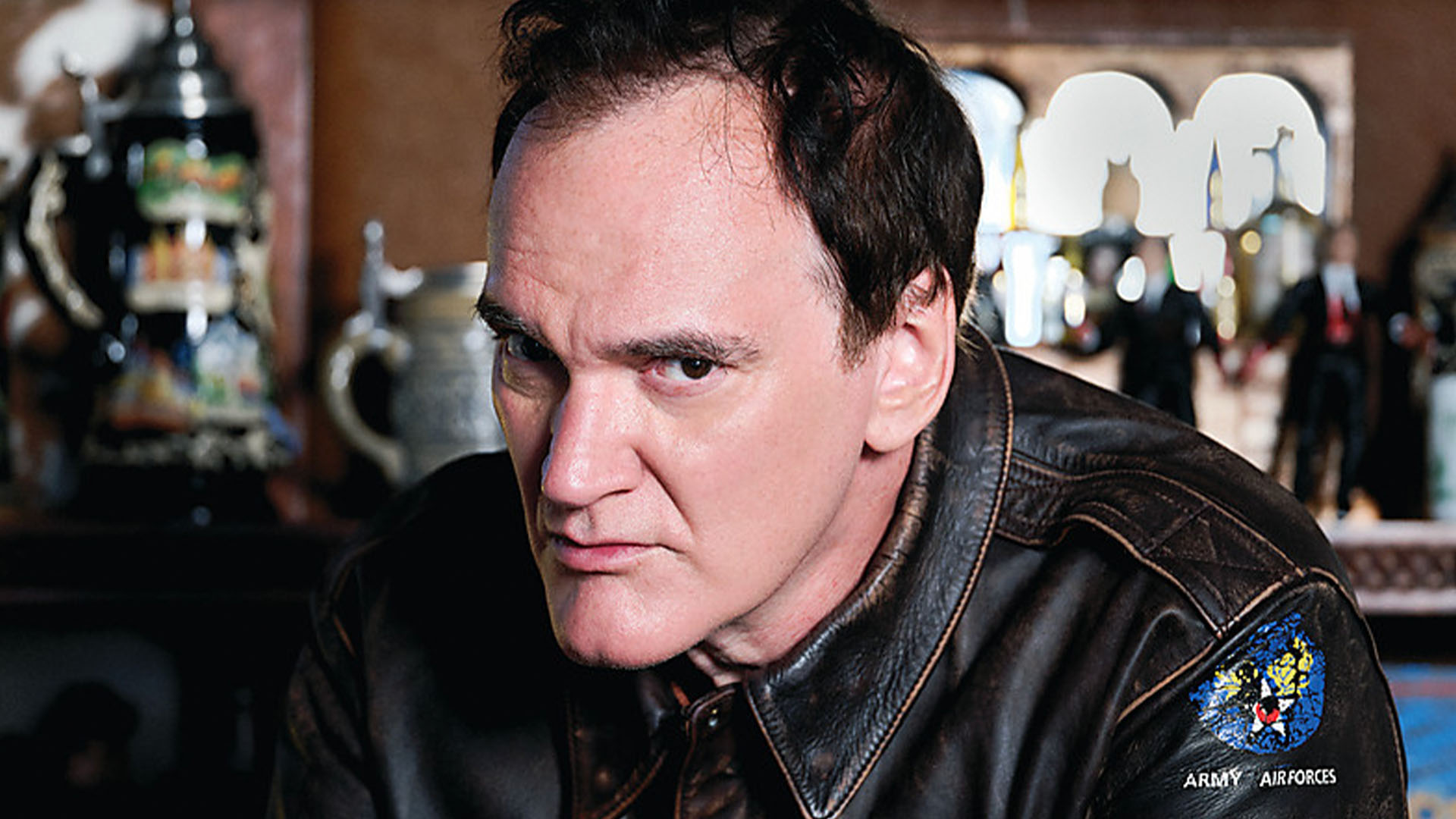

Quentin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation is pure pulp non-fiction

Quentin Tarantino’s “cocktail of personal memoir, cultural criticism and Hollywood history” is here in Cinema Speculation. Adam Fresco gets stuck into the pulp fact within.

Quentin Tarantino’s long-awaited first foray into non-fiction is part film theory, part autobiography. It’s a wildly entertaining ride through 1970s Hollywood from the writer and director of Pulp Fiction and Once Upon A Time in Hollywood.

The, um, speculation over Tarantino’s first non-fiction work is over with the publication of Cinema Speculation this month. It’s a deliriously deep dive into 1970s Hollywood. Part film criticism, part autobiography, and all told with Tarantino’s refreshing passion, immediacy, and fast-moving pace. In other words, it reads just like Tarantino talks in interviews. No bull. No fancy words. No cineaste posing. No film school rhetoric. No university media paper psychological mumbo-jumbo. This is a book any film history and culture fan, Tarantino lover, or 70s movie nut can read and enjoy. A lot.

That Quentin Tarantino should be a captivating writer is no surprise. With four of his screenplays Oscar-nominated (Pulp Fiction, Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood), and two wins (Pulp and Django), plus scores of other international awards, the only real surprise is how long it’s taken the filmmaker to turn to writing in other mediums.

With his tenth and self-proclaimed final movie yet to come, Tarantino has embraced the novel—in 2021 came the publication of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Tarantino’s own novelisation of his ninth movie. A wildly entertaining ride, it fleshed out his lead characters, added a ton of Hollywood movie lore, insight, and reviews, courtesy of Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt’s character in the movie), a stuntman who digs movies, even those arty ones with subtitles. Heck, the novel even featured a guest appearance by Quentin’s stepdad (a real-life Hollywood bar pianist), and mention of Quentin himself, as fiction and fact blurred, just as it did in the Tate-avenging-movie.

Speculating on cinema in his debut non-fiction novel, Tarantino charts a path that owes a big debt to Mark Harris’ 2008 book, Pictures At A Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of New Hollywood. Harris, (the husband of go-to Spielberg screenwriter, Tony Kushner), argued that “New Hollywood” kicked off in 1967, when a host of new directing, acting, and screenwriting talent took over from the Hollywood old guard, eventually replacing monster hits like The Wizard of Oz, My Fair Lady, Gone With The Wind and The Sound of Music with the likes of Easy Rider, The Godfather, Jaws, Taxi Driver, and Star Wars. In QT’s words: “The old studio Broadway musical based extravaganza was finally at long last dead,” to which Tarantino can’t help adding in parenthesis: “(many filmmakers today can’t wait for the day they can say that about superhero movies).”

Harris centres his book on the five films nominated for the 1967 Oscars: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and, um, Doctor Dolittle. Taking his cue from Harris, Tarantino agrees that 1967 heralded a revolution in American moviemaking. Along with those Oscar-nominated movies, 1967 also saw the release of Cool Hand Luke, In Cold Blood, The Dirty Dozen and Valley of the Dolls.

Born in 1963, Tarantino may have missed seeing those movies on their first release, but as soon as he reached seven in 1970, his mother, Connie, saw him as old enough to accompany her and her dates on trips to the movie theatre. Hence, the title of the opening prologue: “Little Q Watching Big Movies,” in which a seven-year-old Tarantino learns to keep his mouth shut during “adult-time,” and only ask questions on the ride home.

QT by turns critiques, reviews, praises, ridicules, debates, and relates facts, opinions, and gossip about a whole host of movies, but the main skeleton on which this body of work is built around is the dominance of “new Hollywood” in the 1970s. In particular Tarantino zooms in on Steve McQueen in Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968), and Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972); Clint Eastwood in Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971); Burt Reynolds in John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972); director John Flynn’s The Outfit (1973) and Rolling Thunder (1977); Margot Kidder in Brian De Palma’s Sisters (1972); Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976); Sylvester Stallone in Paradise Alley (1978); writer-director Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979); director Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1973) and The Funhouse (1981), and much, much, (much), more.

From the famous to the forgotten, the infamous to the obscure, Tarantino’s scope is sweeping, yet always hugely entertaining, informative, and full of the kind of trivia sure to delight movie fans. And boy, does Tarantino know his subject of study. From watching the movies multiple times, to reading contemporary reviews, Tarantino’s celebrity status and high regard in the industry has granted him intimate access to Hollywood insiders. From actors (such as Burt Reynolds, who was originally cast to play the role Bruce Dern ended up playing in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, following Reynolds’ death) to directors (such as Peter Bogdanovich, who helmed The Last Picture Show, and Mask), writers (such as The Getaway screenwriter Walter Hill, who would later become a huge director himself, with hits including The Warriors and 48 Hrs.), and movie critics.

Talking of critics, in one amusing segue, QT even takes time to lambast film reviewers of the 1970s, many of whom he thinks regarded themselves as being above reviewing mere genre fare, and took vengeance by dismissing those movies as mere populist trash. Tarantino tellingly can’t stop himself taking a personal swipe at Los Angeles Times critic Kenneth Turan, who gave Pulp Fiction (and most of the director’s subsequent filmography) a bad review, setting himself up as Tarantino’s nemesis. As the author revealingly notes of his relationship with Turan: “The few times we bumped into each other at an event, we’ve shared a moment of professional mutual rejection that bordered on intimacy.”

Tarantino’s access to, and friendship with, Hollywood movers, players and insiders reaps rewards aplenty. From his chats with Steve McQueen’s former wife, Neile, we learn how she was key to her husband’s success. It was Neile McQueen who read and selected McQueen’s scripts, because he loathed reading screenplays. So much so that later in his career he charged one studio a million dollars just to read a script. Then there’s the tale of how French-Canadian actress Geneviève Bujold missed out on a part in The Getaway. She turned up at a Hollywood bar to meet McQueen, with German actor Maximillian Schell in tow. Turns out Neile McQueen, fed up with her husband’s many affairs, had a fling with Schell, so incensing McQueen that, rather than discuss the movie with Bujold, he instead took her date outside for a fistfight.

And did you know that had Warren Beatty taken the role offered him in classic new-Hollywood Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, he would only do so if the studio cast one Elvis Presley alongside him? Revelations and insights like this are scattered liberally throughout the book, but don’t for a moment think the author is unaware of just how much trivia he’s throwing your way. As Tarantino notes:

“If you’re reading this cinema book, hopefully to learn a little something about cinema, and your head is swimming from all the names you don’t recognize, congratulations, you’re learning something.”

Tarantino is also at great pains to set the record straight when it comes to his take on movie violence. Ever since his debut Reservoir Dogs, Tarantino has been a poster child for pretty much anyone wanting to bemoan the negative social impact of on-screen bloodletting. But for Tarantino, violence in a gangster flick is as necessary as singing and dancing in a musical, or a ponytail in a Steven Seagal movie. When he recounts how, at the tender age of eleven, he watched the violent double-bill of controversial hits The Wild Bunch and Deliverance, he can’t help but add: “But make no mistake, when I tell the story – then and now – I’m fucking bragging!”

Tarantino even compares Dirty Harry director Don Siegel’s forte for “violent brutality,” as opposed to Wild Bunch director Sam Peckinpah’s violence as “a turn away from mere brutality… closer to liquid ballet and visual poetry painted in crimson… It was beautiful and moving.” It’s a fascinating insight into Tarantino’s take on all things cinematic.

Ever wondered about QT’s take on the greatest movies ever made? Wonder no more, because as he says:

“If Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is one of the greatest movies ever made, it’s because one of the most talented filmmakers who ever lived, when he was young, got his hands on the right material, knew what he had, and killed himself to deliver the best version of that movie he could.”

And: “In the sweltering hot Texas summer of ’73, on a threadbare budget in four weeks, with a crew of Texas locals, Tobe Hooper fucked around and made one of the greatest movies of all time, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.”

From The Godfather to Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, from Raoul Walsh to Roger Corman, Warren Beatty to Brian De Palma, John Boorman to Joe Dante, Martin Scorsese to Steven Spielberg, Tarantino’s scope is as widescreen, cinematic, and all-embracing of genre, style, nationality, culture, and content as his own movies. What bursts through every sentence are not just fascinating insights into the author’s life, what shaped him as an adult, and how he thinks, but his abiding passion and sincere love for cinema. Cinema as art. As entertainment. As a source of enlightenment as worthy of serious study as it is kicking back, relaxing, and giving in to the sheer joy of moving pictures combined with sound.

A fantastically entertaining read, I’ve no doubt whatsoever speculating that Cinema Speculation will find its way into the hands and onto the bookshelves of a multitude of movie buffs, cinema students, filmmakers, and fans alike.

Order a copy of Cinema Speculation here