Kenneth Anger’s infamous and scandal-filled Hollywood Babylon

Hollywood history is viewed through a decadent lens in director Damien Chazelle’s Babylon – drawing inspiration from Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, an infamous account of early Tinseltown scandals. Amelia Berry looks at how Hollywood Babylon uncovers something totally fundamental and compelling about our fantasies of fame and excess.

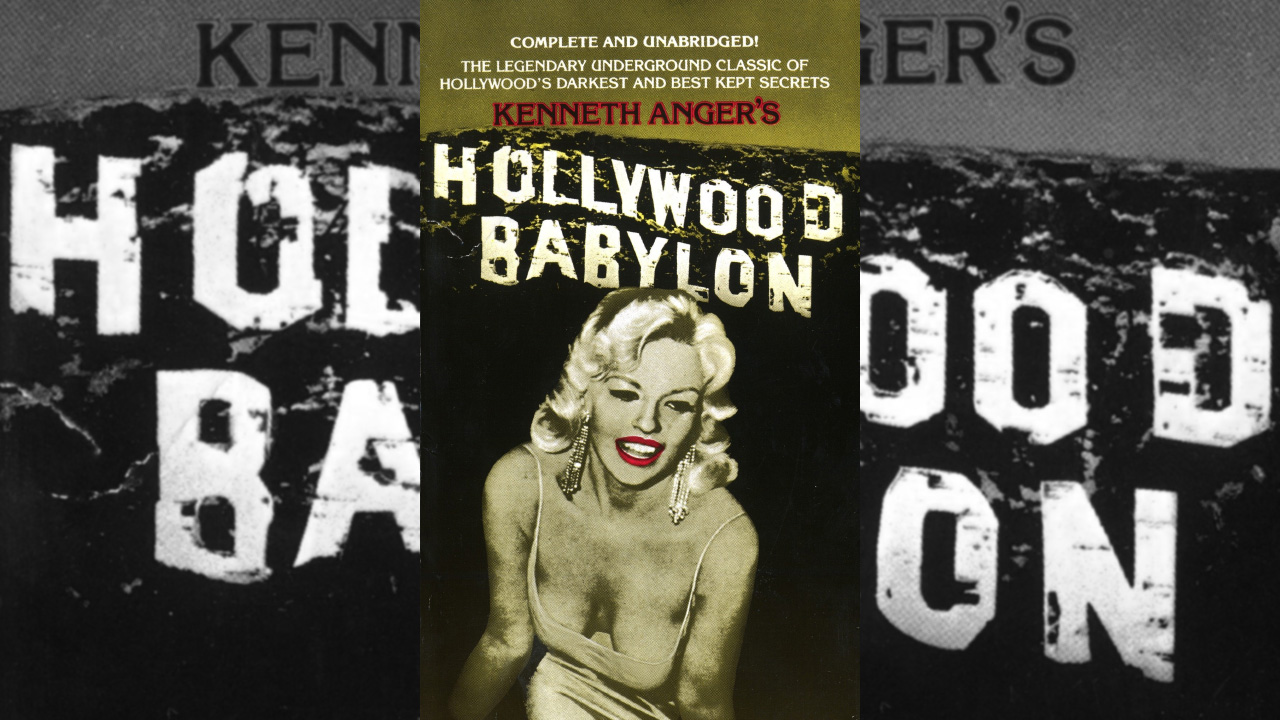

Before E! True Hollywood Stories, before TMZ, and way before YouTube started recommending videos about the actress you hate getting some really terrible plastic surgery, there was a book: Hollywood Babylon, Kenneth Anger’s gleefully vile encyclopaedia of Hollywood Golden Age gossip. With La La Land director Damien Chazelle’s latest epic, Babylon, drawing incidents and inspiration from Hollywood Babylon, it’s worth diving into just what exactly has made this particular tome of hearsay and scandal still hold such fascination more than sixty years after it was written.

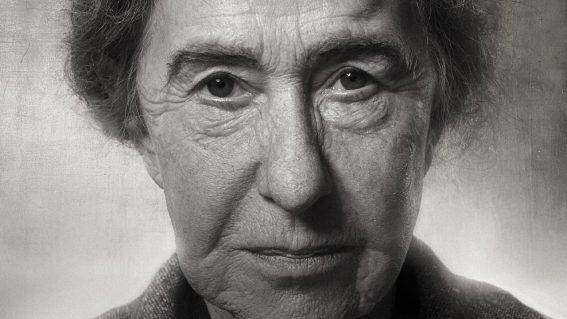

Now pushing 100 and with an impressive “LUCIFER” chest tattoo, Kenneth Anger is an intriguing character in his own right. Born in 1927 as Kenneth Anglemyer, Anger grew up in LA surrounded by the alluring glamour of Hollywood, dancing with Shirley Temple at the Santa Monica Cotillion, and gaining a small role in Max Reinhardt’s 1935 film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. From age ten, Anger began shooting short films on 16mm, and as a teenager became deeply interested in the occult, eventually converting to Thelema, the religion created by the infamous English sex magick pioneer Alastair Crowley.

With the release of the homoerotic silent short Fireworks in 1947, Anger established himself as a filmmaker proper, going on to have a shockingly wide-ranging impact on the direction of American film. His most famous picture, 1965’s Scorpio Rising is another silent short, a montage of sexy gay bikers intercut with images of Jesus, Hitler, James Dean, and Marlon Brandon. Set to a cutesy soundtrack of doo-wop and rock ‘n roll, Scorpio Rising has been hailed by John Waters as the first ironic use of pop music in film.

Directors like David Cronenberg and Martin Scorsese too have claimed the influence of Scorpio Rising (“Martin Scorsese learned about soundtracks from me,” Anger has said), and looking at his other films it’s not hard to draw a genealogy between them and other heavy hitters of 20th-century film. While the song “Blue Velvet” is itself used in Scorpio Rising, it’s striking how much of David Lynch can be seen in the teen idol-soundtracked Cocteau-riff of 1971’s Rabbit’s Moon. The opulent theatricality of Anger’s 1954 film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (featuring a performance from seminal erotic novelist Anaïs Nin) too seems to presage the British art cinema of Peter Greenaway and Derek Jarman.

How then did this luminary of gay underground cinema come to write a book of tawdry gossip about early Hollywood’s biggest stars? Well, as the story so far suggests, it comes hand in hand with some pro-level name drops (and we haven’t even mentioned his friendships with Mick Jagger, Alfred Kinsey, Elliott Smith, Tennessee Williams etc. etc. etc.).

Living in Paris in the 1950s, Anger made friends with then-critics (now legends of French New Wave cinema) Jean Luc-Godard and François Truffaut. Indulging them with the scandalous gossip he’d garnered growing up around Hollywood, they had him write these up for Cahiers du Cinéma (a magazine probably better remembered for birthing auteur theory than for speculating about actors choking to death on dildos). This led to the first version of Hollywood Babylon, written in French by Anger and published in Paris in 1959.

In 1965, the first English language version was printed in America and was immediately banned. When it finally was re-printed in 1975 it had gained a sort of legendary status, with rare copies of the first English edition circulating amongst underground types and people with a taste for filth. Since then, it’s never been out of print and even spawned a sequel, 1984’s Hollywood Babylon II, with a third instalment allegedly written and being legally suppressed by the Church of Scientology.

Drawing its title from Don Blanding’s poem Hollywood, Hollywood Babylon is a kind of historical overview of Tinseltown’s most ghoulish and grotesque moments; from D.W. Griffith’s 1916 Babylonian “bomb” Intolerance to the death of Lana Turner’s boyfriend Johnny Valentine in 1958 (with some additional “Old Hollywood is Dead” material on the 60’s added later).

Told in gloriously arch prose and packed with lurid photographs, the book interweaves quotations from the likes of Alastair Crowley and William Blake with cackling retellings of the truly horrific. Were Lilian Gish and her sister Dorothy in an incestuous lesbian relationship? Was the car crash that killed F.W. Murnau caused by him fellating his fourteen-year-old valet? Just what did Fatty Arbuckle do to hurt that poor girl so bad? These, along with countless tales of suicide, sexual impropriety, drug use, murder, and abortion, fill the pages of the book, Anger flitting from one story to the next with delight and judgement.

Of course, very little of it is actually true. While Anger has claimed that everything in the book was fact-checked (by TWO lawyers), and that the only star who ever took issue with it was Gloria Swanson (suing him for his claim that she had a gold-plated bathtub), he’s also been cited saying that his research method was “mental telepathy, mostly”. Outside of the telepathy, the sources seem to be largely gossip pure and simple, tall tales processed through tabloids, gossip columns, and the rumour mill.

While film historian Karina Longworth has done a brilliant job at debunking several of the more famous stories in Hollywood Babylon in Fake News: Fact Checking Hollywood Babylon (a season of her fantastic podcast You Must Remember This), even just reading the book it’s clear that much of what it suggests is half-truth and baseless speculation. So then, knowing that so much of Hollywood Babylon is just sleazy, mean-spirited fiction, why does it still hold such a strange allure?

While it’s been suggested that Hollywood Babylon is essentially ironic, a gaudy parody of Hollywood scandal and gossip rags, that doesn’t really get at the truth of what the book is doing. If Chazelle’s Babylon has shown us anything, it’s that Hollywood still holds a mythic power, a captivating unreality. While Hollywood Babylon may not reveal much that’s true about real history, it certainly uncovers something totally fundamental and compelling about our fantasies of fame and excess, the idea of Hollywood, the great id of the American unconscious written in light and money.

Before there was Mulholland Drive, before Maps to the Stars and La La Land and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and all the rest, there was Hollywood Babylon. A nightmare to accompany America’s dream factory, where, after all, a good story is worth more than a true one.