The Truman Show at 25: a prophetic story of simulation with a perfect ending

Released in 1998 (just a year before The Matrix), The Truman Show still strikes Luke Buckmaster as a philosophical screen classic: full of big ideas about the cruelty of simulated life, with the ultimate cathartic ending.

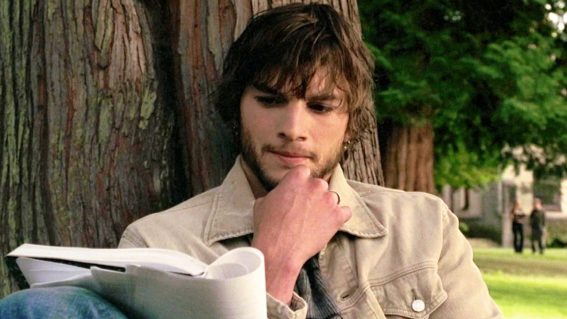

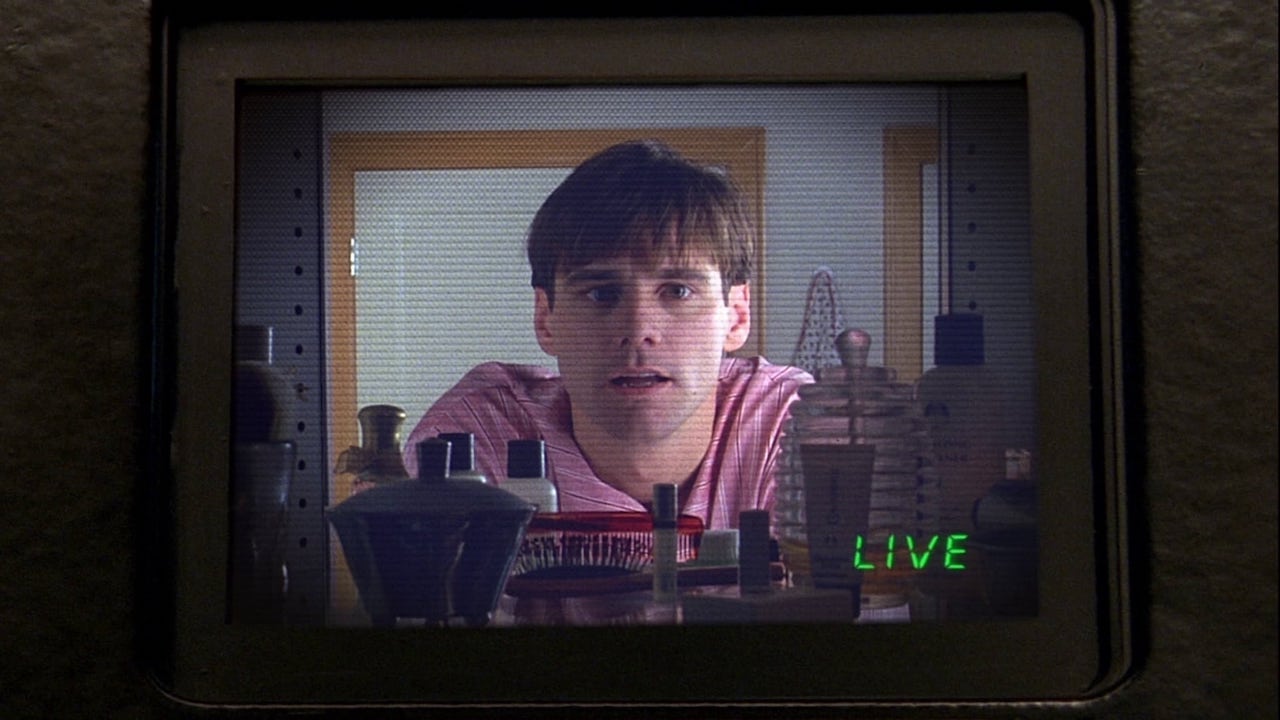

Did Truman Burbank ever entertain the idea that he might be living in a computer simulation? In Peter Weir’s beloved classic, Jim Carrey’s protagonist—unwittingly the star of a TV show that films and broadcasts every moment of his life—experiences a series of surreal encounters. The light that falls from the sky, the shower of rain that follows him around like a spotlight, the cop he’s never met who addresses him by name. If the Wachowski sisters’ consciousness-expanding blockbuster arrived prior to the film’s release (it opened the following year) and was available to Burbank, he might’ve described these peculiarities as being like “glitches in The Matrix.”

Not that he’s much of a cineaste, or allowed to watch whatever he pleases. Films Burbank consumes include old-timey productions such as the fictitious Show Me the Way to Go Home, introduced by a TV presenter as a “hymn of praise to small town life, where we learn that you don’t have to leave home to discover what the world is about.” The director of the show capturing Burbank’s life, Ed Harris’ Christof, manipulates the media around Burbank, screening that film to subliminally suggest he should stay in Seahaven Island (which is actually a huge soundstage visible from space).

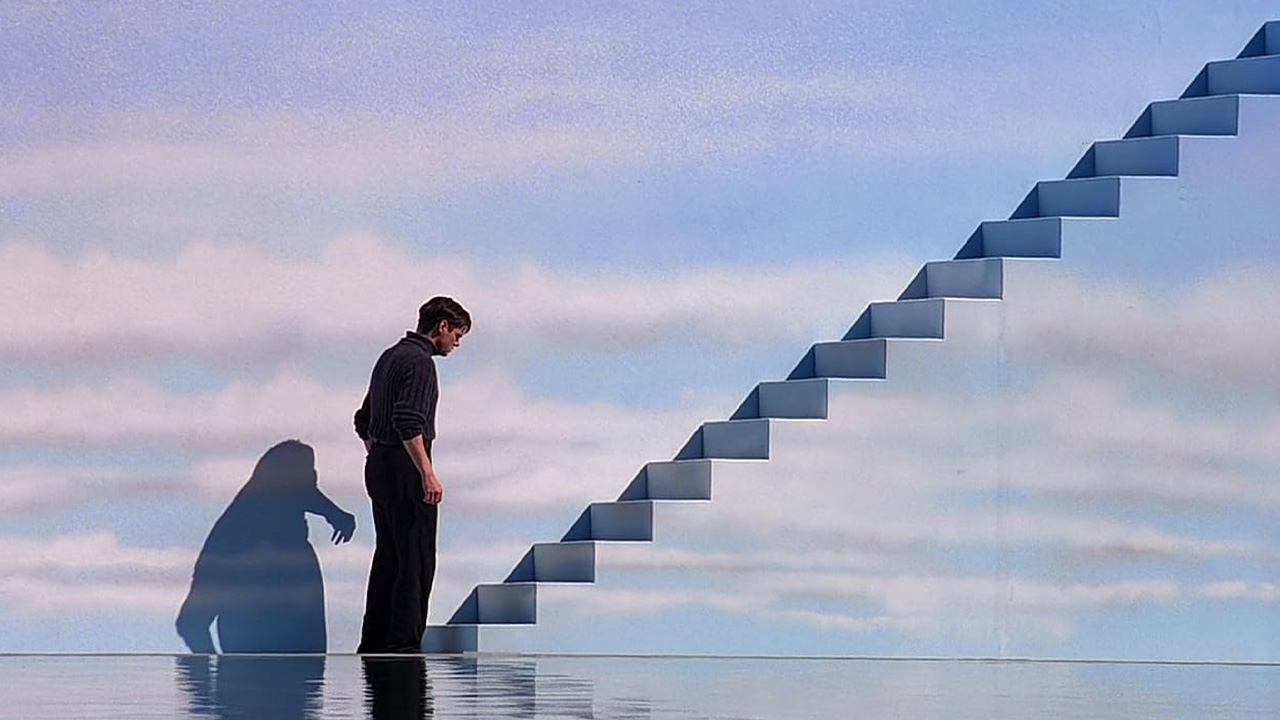

Rewatching the film on its 25th birthday, that moment struck me in a way it hadn’t before—as almost unthinkably cruel gaslighting (like when Burbank’s best friend tells him “the last thing I’d ever do is lie to you.” What a son of a bitch). The media elements inside The Truman Show are simulations inside simulations: Orwellian tools designed to keep the subject repressed, and to prevent the unthinkable: Burbank overcoming his fears and reaching the literal end of his universe. As he does, in a final scene I love to bits, when the protagonist arrives at a staircase leading to a door that delineates one reality from the next.

Thinking about The Truman Show in 2023, it’s clear the film—marvellously written by Andrew Niccol—was ahead of its time in some respects and doomed to be quickly dated in others. I doubt the script would’ve been the same in a post-Matrix world, because the nature of simulations, at least in terms of cultural conversations, changed. If Weir and Niccol were behind, or about to be eclipsed, in that respect, they were ahead in another—pre-empting the reality TV shitstorm that arrived soon after the film’s release, the first Big Brother series (like The Matrix) landing the following year.

Because the genie was still in the bottle, the director and writer’s optimistic—if not naive—attitude towards what would become brain-bleeding backrows entertainment is understandable. Take for example the film’s first words, spoken by Christof: “We’ve become bored with watching actors giving us phony emotions. We’re tired of pyrotechnics and special effects. While the world he inhabits is in some respects counterfeit, there’s nothing fake about Truman himself. No scripts, no cue cards. It isn’t always Shakespeare, but it’s genuine.” One can easily imagine a reality TV producer using similar words today.

The key difference is that reality TV participants are aware they’re in a simulation but Burbank isn’t. In terms of how the subjects behave, this theoretically should change everything, given that the visible presence of cameras dramatically influences people’s behaviour (in this context making them more performative). In a great twist, it doesn’t. Burbank plays up to cameras he doesn’t even know exist, performing in front of a mirror and even delivering his own catch phrase. Niccol approaches the “nature versus nurture” debate by asking: if you were always treated as the star of the show (so to speak and in this case literally) would you act like one? He suggests the answer is yes. Jim Carrey’s casting was clever, his trademark theatricality—toned back but still heightened—having an unusual justification.

Another cultural phenomenon arrived after The Truman Show: 21st century video games. I’m separating things a little conveniently here, because video games existed well before Burbank. Nevertheless, AAA games would increasingly share many of the challenges Christof confronted.

Near the film’s beginning, Noah Emmerich’s character, the actor who plays Burbank’s bestie Marlon (may god curse his swinish face), adds to Christof’s aforementioned speech about authenticity. “Nothing you see on this show is fake,” he says. “It’s merely controlled.” The challenge of controlling narratives that revolve around uncontrollable entities underpins most contemporary AAA games, particularly open world experiences. It’s crucial for developers to create a sense of agency and input. Just enough to sustain an illusion that the player is in control of the experience—whereas, in fact, major outcomes are predetermined.

Christof’s show, like video games, grapples with the tension between storytelling and worldbuilding, exploration and determinism. Like characters in open world productions, Burbank can explore Seahaven and walk around as he sees fit. But when it comes to major plot points (such as those involving his occupation and marriage) he’s given merely the illusion of choice.

Christof wants Burbank to perform like a trained seal, but doesn’t want him to get too adventurous. He certainly doesn’t want him to reach the end of the world—but thank god he does. That happy ending feels entirely earned. The ideas swimming around the film continue to change, but this much will stay the same: we really want this guy, this victim of a terrible cosmic prank, to succeed. We want him to reach the door, turn the handle, and enter the next reality.