Benedict Cumberbatch tries valiantly to puppeteer the sensationally flawed Eric

Very little is left to the imagination in Netflix’s 1980s-set drama Eric—ironic, as the title character is Benedict Cumberbatch’s fuzzy imaginary friend. Luke Buckmaster says the heavy-handed miniseries doesn’t quite come together.

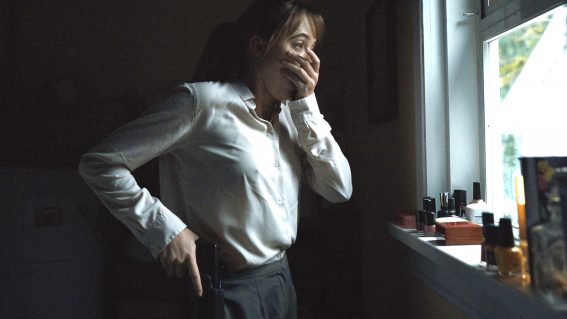

The first episode of Eric, Netflix’s highly ambitious and sensationally flawed series written and created by Abi Morgan, begins like any missing person drama, Benedict Cumberbatch’s haggard father Vincent pleading in front of cameras for his child to return and “prove to all these ladies and gentlemen of the press that you’re not dead.” But it ends very kookily and idiosyncratically: Vincent’s latest drawings—fleshing out sketches made by his missing nine-year-old son Edgar (Ivan Morris Howe)—magically bring to life the titular character: a massive, fluffy plaything that looks like an employee of Monsters Inc.

Vincent is a puppeteer, and the creator of an iconic children’s series called Good Day Sunshine. It’s soon ascertained that the James P. Sullivan or Ludo-like Eric can be seen only by him, which pushes the drama into a portrait of mental illness. The hard-drinking and intemperate Vincent is sane enough to know that speaking to Eric in front of others will reveal his craziness, though he can’t help but address his imaginary companion with curt directives or outright condemnation: “did anybody ever tell you you’re an asshole?” he says on the train, a nervous commuter watching on.

Eric’s not the nicest of imaginary friends: “you’re the shittiest shit bag of a dad,” he says, obviously intended to bring to the surface the emotionally ravaged protagonist’s inner guilt. Their interactions are funny weird, not funny ha-ha. Although one of Eric’s first lines is amusing (“let’s go find yer fuckin’ kid!”) any potential humour going forward gets smothered by director Lucy Forbes’ morose tone and sticky, moody aesthetic.

Vincent believes he can somehow save the day if he puts Eric on his TV show; it’s around this point his wife Cassie—impactfully played with limited screen time by Gaby Hoffmann—realises her husband might be a little non compos mentis. More helpful are the efforts of a gay black detective, Michael Ledroit (McKinley Belcher III), whose partner is dying of AIDS, and who—obsessed with cracking the case—becomes an increasingly prominent character going forward. Set in the 1980s, the show broaches meaty subjects including homelessness and the AIDS epidemic, which again speak to Morgan’s ambiguous scripting but clog up the story, making it feel heavy and lumbering.

It doesn’t take long before two core elements—Vincent and Eric’s relationship, and Michael’s investigations—begin to feel ill-fitting. Perhaps the logic was that the latter grounds the story while the flighty former sends it to space, theoretically providing yin and yang. But that dichotomy works against it: the left hand doesn’t seem to know what the right is doing, and it’s hard to say which gets in the way of the other. Eric’s presence becomes stranger, partly because he’s quite seldom seen—like a lazy apparition that can only be bothered haunting its victims once in a while.

Presenting the giant furry monster as a series of hallucinations, reflecting Vincent’s declining health, is one of the least interesting approaches to ushering a child’s creation into adult existence. Far less interesting for instance than having a bong-smoking teddy bear occupy a “real” place in the narrative world, like in Ted, or having a mentally unwell person operating a puppet and speaking only through them, as Mel Gibson does in The Beaver.

There’s also the wonderful 1950 film Harvey, in which James Stewart plays a drunkard followed around by a six foot imaginary rabbit. Unlike Eric that film skirts conventions: for starters the protagonist is a kind drunk, not a mean one—alone an interesting proposition given how many terrible boozers there are on screen. And while we don’t see Harvey, people do inside the film, which indulges in fantastical elements without spelling them out visually, allowing Harvey to exist in our imagination. By the third or fourth time I watched it, I almost felt I too could see the lanky big-eared scamp for myself.

Very little is left to the imagination in Eric, which is unsubtle and increasingly heavy-handed, ultimately (this review encompasses all episodes) veering into didacticism, Vincent having the cheek to lecture us about how real change begins with yourself. Its biggest asset is Cumberbatch’s performance: this guy is painfully good at portraying broken, drowning people, who reach out for help and bring others down with them.