History-making Sudanese drama Goodbye Julia is a class act

Two women from different parts of Sudan form an uneasy friendship in Goodbye Julia. Liam Maguren calls it a class act of a drama that echoes loudly to the wider state of the country.

Full-time aircraft engineer and part-time filmmaker Mohamed Kordofani has gone above and beyond to create history-making cinema with his feature debut Goodbye Julia. It’s the first Sudanese film to premiere at Cannes and win an award at the festival, taking home the Freedom Prize for its meticulous story of two women who cross paths through chance and tragedy set right before the nation voted to separate North and South in 2011. This class act of a drama relishes in small details, concocting a compelling clash of classes that echoes loudly to the wider state of the country.

The film wastes no time with the setup. Well-off Northerners Mona (Eiman Yousif) and Akram (Nazar Goma) hunker down in their lavish home while Southern protesters storm the streets. Southerner Julia (Siran Riak) and her family are kicked out of their home because of the riots they didn’t take part in, forcing them to dwell in a makeshift shelter. More dominos fall until Mona inadvertently leads Julia’s husband to a gun-wielding Akram, who all-too-easily shoots in supposed self-defence.

Crumbling with guilt but unwilling to tell anyone the truth about the incident, Mona instead attempts penance by hiring Julia—who thinks her husband’s missing—as a maid, which includes accommodation for her and her son. As the weeks roll on, an uneasy friendship grows alongside Mona’s lie (which sits on top of her other lies).

Kordofani doesn’t hold back with his depiction of the racism lurking in Sudan. Goma’s tightly controlled portrayal of Akram illustrates a man whose institutionalised hatred has become such a comfortable part of his identity that not even affection can shake it. Akram doesn’t hesitate to call Southerners “slaves… savages… dogs…” but he’ll also take on a caring uncle role for Julia’s son, desperate to be a father himself someday. On paper, it makes no sense, but Goma makes us believe in a character cemented in his contradictions.

One potent scene sees Akram and Mona debating these racist attitudes, each using the words of their prophet to back up their points. Mona clearly feels Southerners are being hard done by, but Akram astutely points out her hypocritical nature as a woman who lives in comfort while her Southern maid lives in a poorly ventilated sleepout. Akram’s point holds some validity—their joint comforts come at the cost of others—but at least Mona shows a willingness to change.

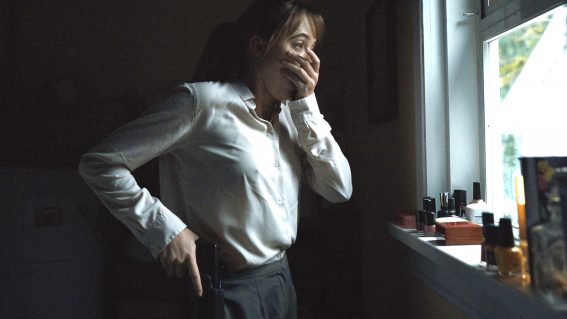

While she’s not the titular character, this is really Mona’s movie, and Yousif excels as a woman navigating the complicated crossroads of hate and love, truth and lies, good and evil. Cinema’s plagued with films about people withholding lies, a device used to artificially generate tension until its inevitable conclusion, but Yousif’s ability to conduct the internal fears of her character generates a palpable empathy towards Mona and an uncertainty about the story’s conclusion. The more we learn about Akram’s controlling nature, the more we understand Mona’s history of lying as a means of survival, as well as the rigid gender roles that hold Sudanese women back.

It does not excuse Mona’s actions towards Julia, but it adds a hefty amount of psychological weight that presses down in every moment of the film. Riak remains absolutely radiant as Julia, maintaining the dignity and valour of a woman determined to do the best by her son no matter the circumstance. But her lightness only further crushes Mona’s conscience—a quality she hides as their friendship matures. Mona shares some of her privileges with Julia, and Julia introduces Mona to a type of freedom she’s been denied, but the power dynamics are never fair, the friendship tainted by being partially transactional.

Perhaps things would be different if they weren’t living in the residue of a 50-year Civil War. Though, as Julia states, the war is over, but not over, if you catch her drift. The film’s final shot backs this up with one of the most quietly devastating images you’ll see this year. Kordofani shot the film in Khartoum right before the capital city plunged back into warfare, and when the credits roll, you can’t help but think he saw this coming.