Michael Mann’s Ferrari oozes with glamour, balancing motorsport thrills and melodrama

Adam Driver is Italian sports car entrepreneur Enzo Ferrari in Oscar-nominated filmmaker Michael Mann’s biopic. Mann steers the melodrama into a riveting portrait of a man who is hyper vigilant about his career, his cars, and his public persona, writes Cat Woods.

Director Michael Mann’s Ferrari exists in a gradual, prolonged sunset. There is a sense that the day—and all its potential—is drenched in the amber hues of evening: orange, gold, and yellow. Even faces glisten with a romantic, sepia sheen in the many near-claustrophobic close-ups on noses, eyes and lips.

Inevitably, once the sun sets, darkness looms so there is only this brief window for Enzo Ferrari (a distinguished Adam Driver) to prove his acumen professionally, and his reliability as a father, a husband, a trusted public figure before the light is gone. He is, as he admits to the head of Fiat, the founder of an Italian icon, “a jewel in the Italian crown”. Copious shots of pasta, churches, red wine and ornate villas remind us, Ferrari is Italy (moulded in sleek, glossy metal).

Over three months in 1957, Enzo Ferrari’s life concentrated more soap opera-level drama than a year of The Bold and the Beautiful. It is this period that forms the narrative arc of Ferrari. The 59-year-old Italian founder of Ferrari is attempting to salvage his relationship with wife and business partner Laura (Penelope Cruz), who has just discovered Ferrari’s secret family with Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley). He faces bankruptcy unless he can salvage the credibility of Ferrari through triumphant performances in the ruthless Mille Miglia race from Brescia to Rome and return (1000 miles). He is at a professional cliff edge, and he is also heartbroken: it is only a year since his beloved son, Dino, died of muscular dystrophy aged 24.

It’s everything all at once, and director Michael Mann steers the melodrama into a riveting portrait of a man who is hyper vigilant about his career, his cars, and his public persona despite the terrifying split-second potential for everything to go up in flames. The same acute level of control he attempts to wield over his drivers cannot be extended to his romances, his children, or his business, and sacrifices are inevitable.

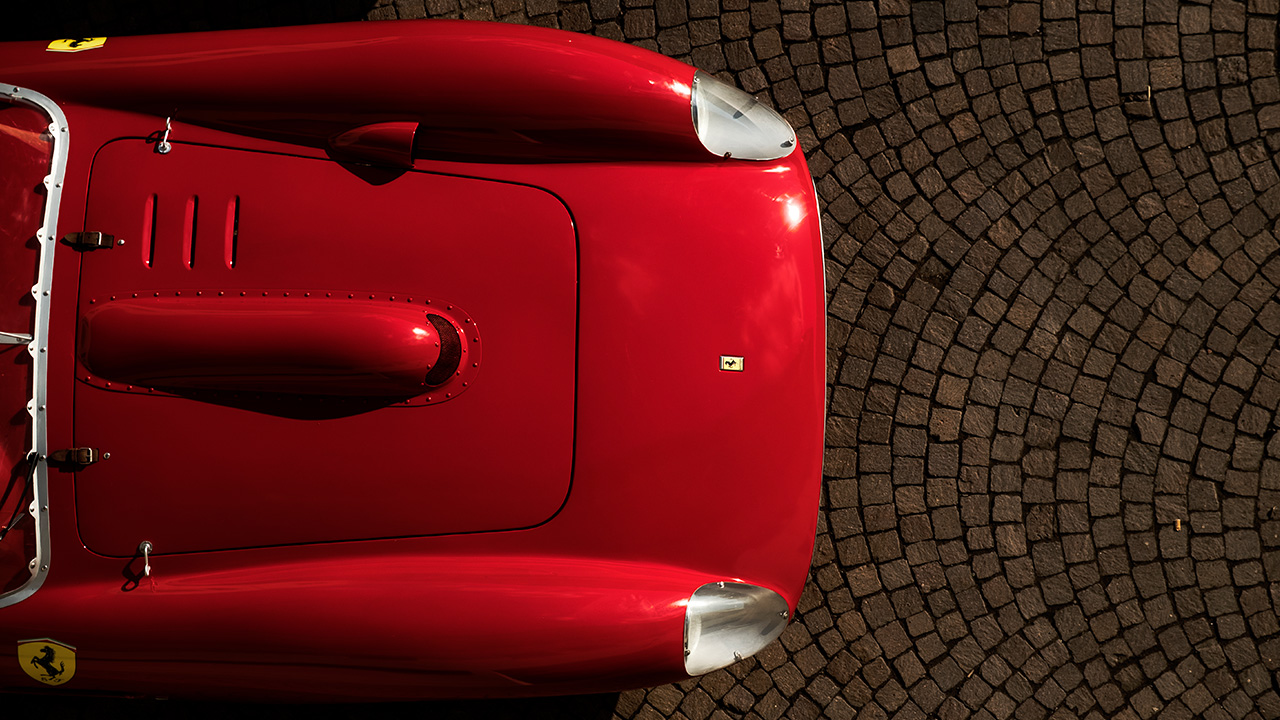

Mann is an unabashed racing car fanatic, and the scenes in which drivers are whipping around curves, pumping the accelerator to near-inhuman speeds, and balancing their lives precariously on a nanosecond choice of when to brake are thrilling. If this were a movie dedicated only to life on the track, or a blow-by-blow account of Ferrari’s life in cars, it would still be compelling under Mann’s instinctive eye for scene composure, light, colour and movement.

He is near-fetishistic in his embrace of colour and form, and Ferrari oozes with glamour: curvaceous, lipstick red cars; lush green hills of Northern Italy; tailored three-piece suits; slicked-back, perfectly polished hair; the gleaming silver perfection of an engine.

Thankfully, Ferrari is not merely an homage to cars. It is a snapshot of Ferrari’s life during a make-or-break period that tells us so much about who he was, who he is, and what he stands to lose if his drivers fail to win and his personal secrets are exposed. Based on Brock Yates’s biography Enzo Ferrari: The Man and The Machine, this movie was a long time in the making (with Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale set to play Enzo at respective points).

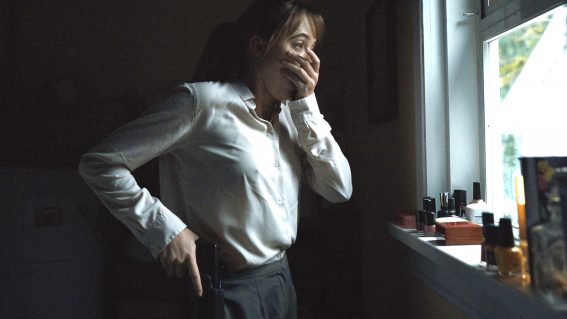

Driver’s casting is a coup, though. He has the gravitas, in his long, lean physique, drawn cheeks and downcast face to portray the beleaguered Ferrari. His Italian accent is dubious at best, though it does improve as events pick up momentum and Ferrari must be a coach to his drivers, a stoic face to the press cameras, and the worthy leader of an Italian automotive icon.

As Laura, the Oscar-winning Penélope Cruz steals every scene she’s in. Her portrayal of grief-stricken, traumatised but resilient women in Pedro Almodóvar’s movies left little doubt she would find the same emotive qualities in Laura’s story. It would be easy to overdo the part, with tantrums and wailing at the ingloriousness of Enzo’s betrayal, but Cruz knows when to reign in her expressions and the power of a trembling lip or glistening eyes. The way she looks at her husband is heartbreaking—he is both her lover and her hero. The weight of losing her adult son, and his father a year later is almost too much.

Shailene Woodley, too, brings her A-game, but she is well-practiced in playing a resilient single mother (which she sort of is, as Enzo comes and goes at his leisure). She was a standout in Big Little Lies, carrying horrific secrets with a stiff upper lip, and battling for respect amongst affluent, perfectly poised women. As Lina, Enzo’s lover and the mother of his child Piero, she is torn between her love for Enzo, and her vision of a life with him that isn’t a shameful secret.

Midway through the movie, Ferrari confronts his elite racers, who have not delivered winning performances. They do not have the deadly instinct to win, he opines. They must be willing to win at all costs, that is their obligation to their job. As he explains to his young upstart recruit, Alfonso de Portago (a wonderful Gabriel Leone), “Two objects cannot occupy the same point in space or the same moment in time.”

To a degree, imperfectly, Mann has defied Enzo Ferrari’s own theory. In Ferrari, he has evinced the story of an ambitious, unwavering businessman and car racing fanatic while also revealing the very human sacrifices and consequences of betrayal, grief, fatherhood and faltering romance. The precarious balance to hold both in the same time and space takes a deft hand. Mann has managed it.