Scary, funny, and not too stuffy, A Haunting In Venice is Branagh’s best Poirot mystery yet

Kenneth Branagh calls up some famous mates and whacks on another moustache for A Haunting In Venice, the latest of his Poirot murder mysteries. Eliza Janssen says it’s an improvement on the past two, bigger Christie adaptations.

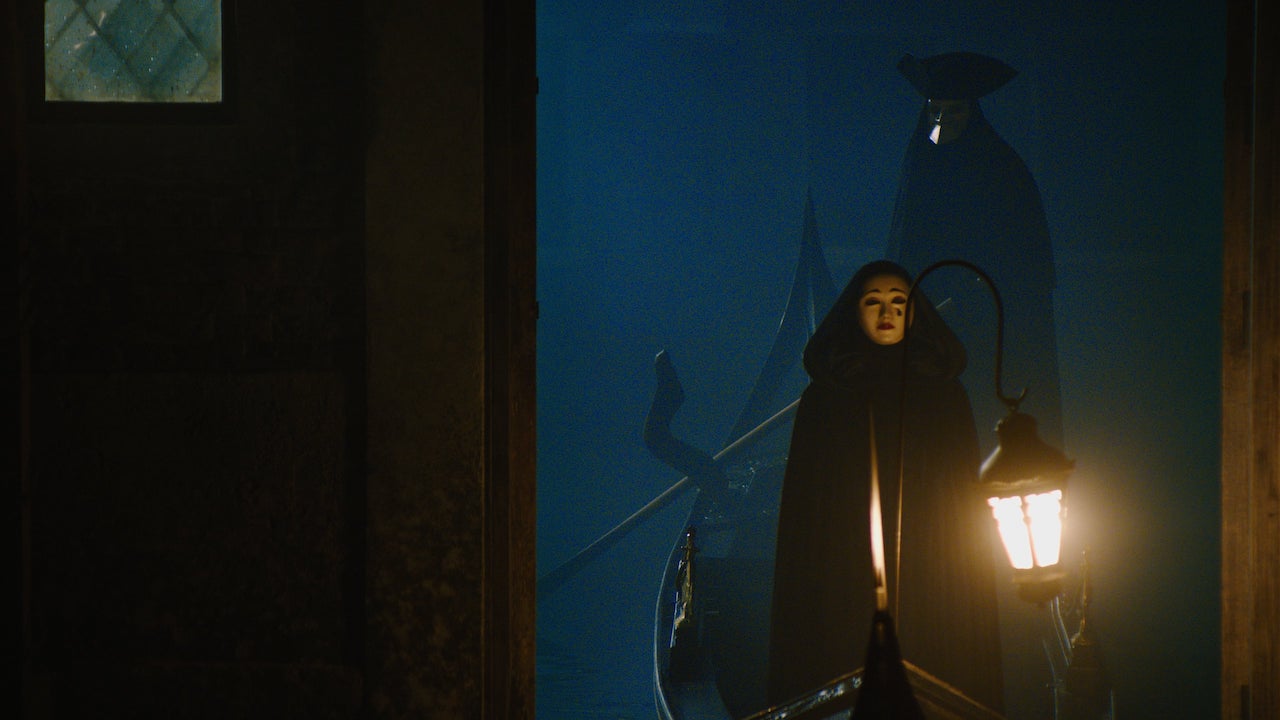

Venezia! A city of labyrinthine canals, ornate plaster masks, and a pervasive mouldy smell that my disappointed tourist mother constantly brings up whenever the city gets mentioned. It was the site of some Ethan Hunt tom(Cruise)foolery earlier this year, and to me it’s best remembered as the somber setting of Don’t Look Now. Taking us back to the city’s post-WWII state, shrouded in funereal fog, Kenneth Branagh’s latest Poirot film is less of a sightseeing jaunt and more a Gothic, jumpscare-laden sleepover.

The British director’s two previous efforts at adapting Agatha Christie’s timeless Poirot mysteries to our modern screens have felt bloated: held back by attempts at respectability, self-seriousness, adherence to moustache-waxing tradition. I reckon A Haunting In Venice is the best of the bunch yet, even with its less-starry cast and more contained murder-mystery.

Say goodbye to the flimsy CGI landscapes of Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile, and ciao to a more intimate, downbeat, indoorsy detective story. Those other spectacles were bound up in being faithful to their source material—Christie classics with twists and reveals that fans of the beloved David Suchet TV series will already know off by heart. By choosing to adapt the relatively unloved novel Hallowe’en Party, Branagh gives himself more creative license, entirely changing some characters and transplanting the setting to Venice’s haunted palazzos and gloomy gondola rides.

Branagh’s Poirot movies have wrangled less red carpet talent with each instalment: we went from Michelle Pfeiffer and Johnny Depp (yeesh), to Gal Gadot and Armie Hammer (double yeesh), to Haunting‘s biggest names being recent Oscar-winner Michelle Yeoh, Jamie Dornan, and Tina Fey as the Belgian sleuth’s old friend. While it takes a while for us to warm to Fey’s screwball sass, she gradually becomes a welcome spanner in the works of Poirot’s retirement.

Now lazing on riviera rooftops eating pastries and grieving those he’s lost, the detective needs Fey’s mystery writer Ariadne Oliver to give his career a motivating kick up the bum—in the direction of a wealthy opera soprano’s (Kelly Reilly) Halloween seance. The fragile mother is mourning the death (suicide? Murder? Ghost vengeance?) of her daughter, assembling a motley crew of friends, believers, and hastily invited skeptic Poirot to witness her return from the afterlife.

Yeoh steals the show as the medium at the centre of this spooky session, bringing a sense of dark poise to what might otherwise be the funniest outing for Branagh’s egotistical Poirot. Beyond her psychic hysterics in the film’s overlong first act, it’s the younguns who stand out amongst the cast. Emma Laird and Ali Khan are affecting as the spiritual madam’s Romani assistants, yearning for a better life in the US. And Branagh’s Belfast star Jude Hill is adorably eerie as a kind of Mini Poirot. Or Mini Colin Robinson, maybe. The kid is believably wise beyond his years and seriously needs to touch grass.

Contained to the course of one night in a creaking, flooding old manor, A Haunting In Venice‘s whodunnit might fail to satisfy amateur sleuths who like their mysteries to properly wind and weave along the contours of our suspicions. Once the seance goes grimly wrong, Poirot is cursed with auditory and visual hallucinations of creepy ghost children, and Branagh’s filmmaking is never bold enough to convince us that there may be something truly supernatural afoot. The director has asserted that this latest Christie romp is a “supernatural thriller”, rather than an outright horror movie, and some limp, under-realised bits of scary CGI here and there seem to suggest that Branagh really doesn’t have much interest in going full giallo.

That’s not to say the film has no style at all, though. Cinematographer and returning Branagh collaborator Haris Zambarloukos has been an absolute madman with kooky Dutch angles in the previous Poirot flicks, but they at least make sense here, canting the tall ceilings and narrow hallways into expressionist new shapes. Sure, there’s some wacky shots that totally throw off our suspects’ proportions—making Poirot look hilariously tiny and big-headed when shot overhead in a doorway, for instance. But a little grotesquery adds to this bump-in-the-night environment, even if some needless upside-down moments feel like showboating rather than storytelling.

Despite some genre-hesitant stuffiness and obvious creative decisions, A Haunting In Venice still feels more substantial than the other two Poirot adaptations. There are enough nifty little clues that lock into a satisfying bigger picture, and Poirot’s arc—of regaining his faith in justice and jolting back into his former wit and logic—gives the film a personal momentum that felt pointless back in Nile‘s silly black-and-white opening backstory. Perhaps the little European PI with fine facial hair should delve back into X-Files territory again sometime: I’d love to see him face off against Bigfoot.