A guide to giallo, the horror genre inspiring Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho

As Last Night in Soho hits more streaming services, we revisit Tony Stamp’s exploration of giallo – the genre from which Edgar Wright’s film draws its key inspirations.

Last Night in Soho

There’s an image being used to market Last Night in Soho that features Thomasin McKenzie looking shocked, her wide eyes ringed with running mascara. To a certain type of filmgoer, this image is clearly influenced by the Italian genre known as giallo, which hit its peak in the 1970s. But explaining what giallo is can be tricky.

The word means ‘yellow’ in Italian, due to the yellow-covered crime novels the genre was influenced by, and became a catch-all term for mystery fiction. But to cinephiles, particularly those outside Italy, it means a certain set of aesthetics: bold lighting and eye-popping colours—particularly bright red blood. Wobbly dubbing. Abrupt tonal shifts. Nudity. And definitely a leather-gloved killer.

The killer will remain anonymous till the last reel, and will probably be someone you forgot about. We’ll see the murders from the perpetrator’s point of view (POV). Any time a scene features a character alone, they will almost certainly die.

Like the American slasher movies giallo predated and influenced, there seems to be an endless supply of old gialli waiting to be discovered, and to fans, watching them is like pulling on a familiar, somewhat worn sweater. The tropes become comforting—wonky performances, red herrings, a generous dose of seventies sexism—all familiar elements of the giallo experience.

To help navigate the genre, I’ve chosen ten films, each by a different director, as a series of signposts along the journey.

Blood and Black Lace (1964)

The consensus is that Mario Bava’s 1963 film The Girl Who Knew Too Much is the first official giallo. In 1970 he gave the genre a massive shakeup with the bloody murder setpieces of A Bay of Blood. Blood and Black Lace might be his most stylish effort though, which is appropriate given that it takes place in a fashion house where models are mysteriously dying.

Bava was clearly a major architect of the genre, and his bold use of colour influenced fellow horror titan Dario Argento, as well as many modern filmmakers including Edgar Wright, who prior to Soho had included giallo elements in Hot Fuzz. James Wan’s Malignant also springs to mind as a recent riff on these tropes.

So many hallmarks of horror cinema are already in place in Blood and Black Lace: a broken sign creaks in the rain. The lighting grows gaudier during the violent scenes, and the music gets rowdier. There are lingering closeups of murder weapons, and of course leather-gloved hands.

The killer is a bit less terrifying than later iterations, wearing a stocking over his face and a fedora hat, but despite minimal blood the deaths are gnarly—a victim getting spiked through the face is shocking now, nevermind 1964.

Short Night of Glass Dolls (1971)

This one features a fantastic, horrific framing device—our hero is presumed dead and shipped to the morgue, but he’s very much alive, trapped in an unresponsive body, and we’re privy to his increasingly desperate thoughts. He narrates the bulk of the movie as we flashback to the days prior, when his girlfriend (future Bond girl Barbara Bach) goes missing, but the film keeps cutting back to the morgue as his friends identify him, he’s taken to the autopsy table and so on. The clock is ticking as he tries to remember how he wound up here, and it’s genuinely unnerving.

Director Aldo Lado deploys rapid cuts to show the lead’s memory returning to him throughout, unsettling and trend-setting, and the whole thing sticks in your gut because it’s so damn bleak, like a particularly nasty episode of The Twilight Zone.

The Fifth Cord (1972)

A beautifully coiffed and moustached Franco Nero (Django himself) plays an alcoholic reporter targeted by a killer prone to leaving creepy voice messages, which contain riddles about a party the victims all attended.

In contrast to the huge output of many giallo directors, Luigi Bazzoni only made five films, and The Fifth Cord never feels like a cash grab—it’s a sturdily constructed thriller with cinematography by Vittorio Storaro, who shot Apocalypse Now, and features a wonderfully discordant score by Ennio Morricone. On the respectable side of the genre but a great example of many of its trappings.

Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972)

Lucio Fulci’s career started in the late fifties making crime films, and peaked twenty years later with gross-out classics Zombie Flesh Eaters, City of the Living Dead and The Beyond. A real journeyman, he dabbled in Westerns, war films and sci fi, and cranked out some notable gialli—the phantasmagorical sleaze-fest A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, the controversial and condemned New York Ripper, and this small town freak out.

It was only 1971 and Fulci was not mucking around—there are two infamous scenes here, one involving a woman beaten with chains (soundtracked by a nearby radio station—odds are very high Tarantino saw this film), the other an attempted seduction of a pubescent boy by very nude genre legend Barbara Bouchet.

Fulci wallows in the muck, but the mystery is engrossing, culminating in a pointed swing at the Catholic Church. He also shoots the heck out of it, with faces in closeup surrounded by the blues and greens of the Italian countryside, strategic split-diopter shots complemented with oppressive sound design (the drone of cicadas throughout), and feverish editing (sometimes cutting away mid-sentence).

The movie also has a wonderfully satisfying, seemingly endless dummy-thrown-off-a-cliff finale, truly one for the ages.

What Have You Done to Solange? (1972)

The creep factor is off the chain here, with a plot that involves a high school teacher sleeping with one of his students. A shot of the couple framed with her uniformed schoolmates in the background is followed by a shower scene that offers up teenaged body parts like a pervert buffet, the sort of cognitive dissonance that runs rife in some of these movies.

Once the young girlfriend is [SPOILER] murdered, the teacher teams up with his estranged wife to crack the case. It’s all very twisted, the killer favouring a murder method too offensive to describe here, but the typically convoluted plot offers up a neat resolution in the end. Set in London for some reason, director Massimo Dallamano gets in plenty of run-and-gun location footage to go with the very Italian black glove/POV shenanigans.

Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972)

Unwieldy giallo titles flew so that this one could soar. An author sloshes drunkenly around his mansion, hosting sex parties and muttering things like “It’s so easy for teenagers to think they’re something, when in fact they’re nothing”, and before long the funky murder music has started and the throat slashing has begun.

When genre legend Edwige Fenech shows up claiming to be his niece, everyone’s motives become muddied. Sergio Martino also directed giallo classics Torso and All The Colours of the Dark (which came out the same year), but this one stands out, and not just for that outstanding name.

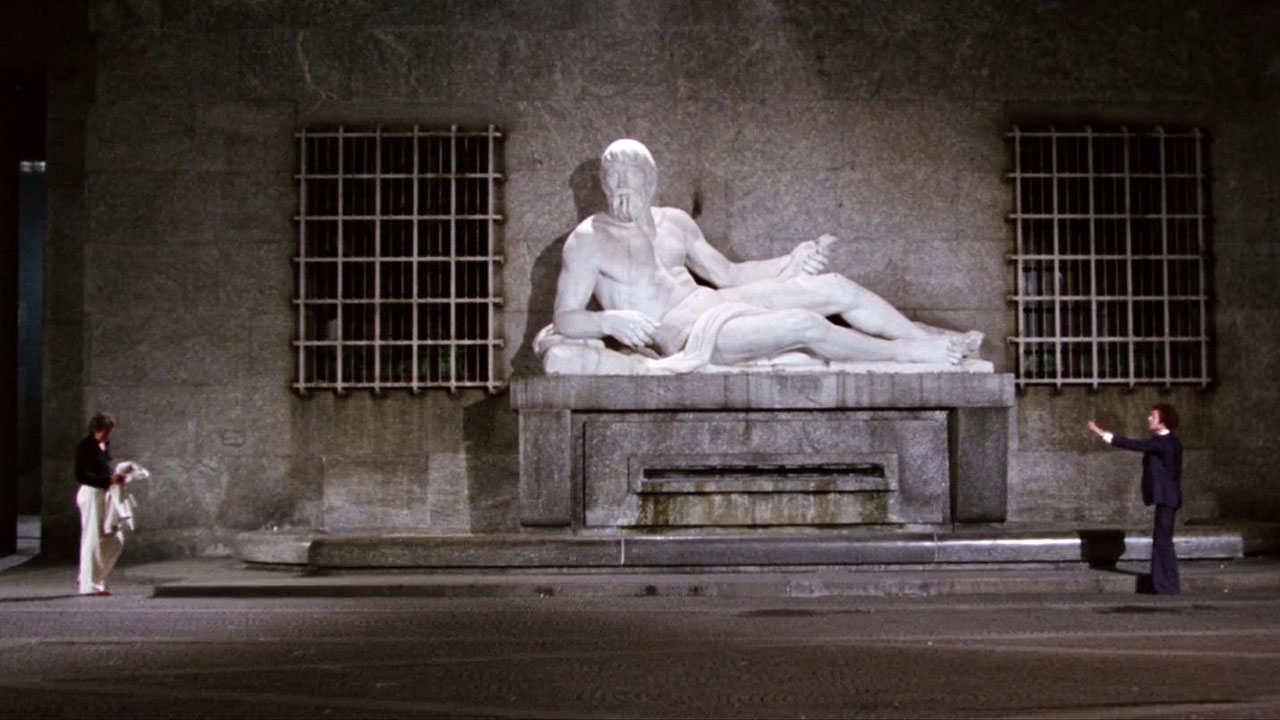

Deep Red (1975)

Dario Argento’s 1970 film Bird With the Crystal Plumage was credited as popularising the giallo craze (as well as giving birth to its lengthy titles), and five years later he delivered one of the genre’s definitive works, employing the masterful use of empty space and shadow he would go on to perfect in 1977’s Suspiria.

Deep Red also marks the director’s first pairing with prog-rock band Goblin, which wound up being a longstanding partnership. It’s easy to see why—the band’s sometimes counterintuitive approach of busting out a danceable drum beat during scare sequences is so good it makes watching a man scraping plaster off a wall into riveting stuff.

Characters are dwarfed by buildings and sculptures. Cassette tapes and vinyl records are fetishised via lingering closeups, as are leather gloves and mascaraed eyes, Argento honing in on giallo’s cinematic language to unsettle and implicate his audience.

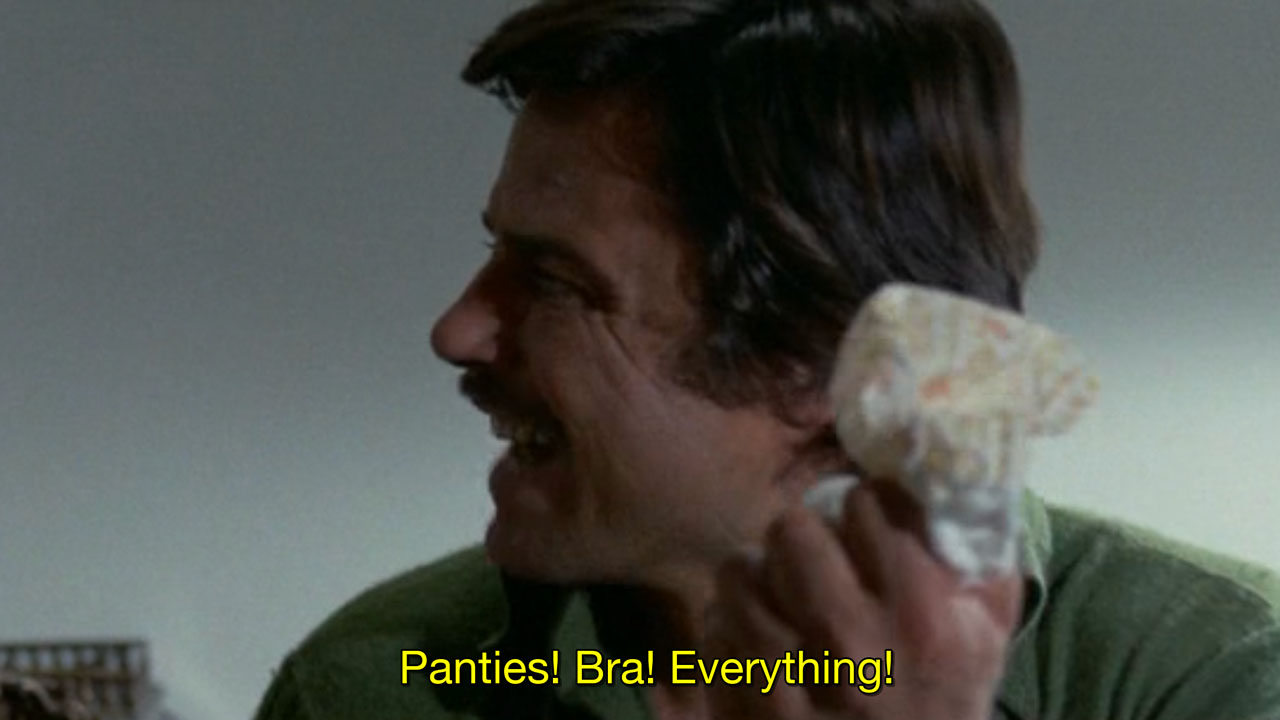

Strip Nude For Your Killer (1975)

The same year as Deep Red, one of the genre’s grubbiest efforts was unleashed. Andrea Bianchi’s aptly-titled serving of sleaze literally starts with a shot of a woman’s pubis and only gets pervier, but manages to wedge in a pretty good yarn alongside all the skin.

It’s another one that seems to self-critique as it goes—every man is a pervert and a predator, especially photographer lead Nino Castelnuovo, who once starred in Jaques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and who we meet here coercing a stranger into sex in a public changing room. This happens just after his friend has looked her up and down and commented—I shit you not—“I want my mommy”.

It’s real ‘take a shower afterwards’ stuff, but the more male characters we meet—sweaty abusers every one—the more you start to wonder if Bianchi is… having a go at the patriarchy? Then the film goes back to treating Castelnuovo as a loveable rogue—even after he’s physically abused his girlfriend—and you remember what you’re watching. Needs to be seen to be believed, in all its disgusting, shameless glory.

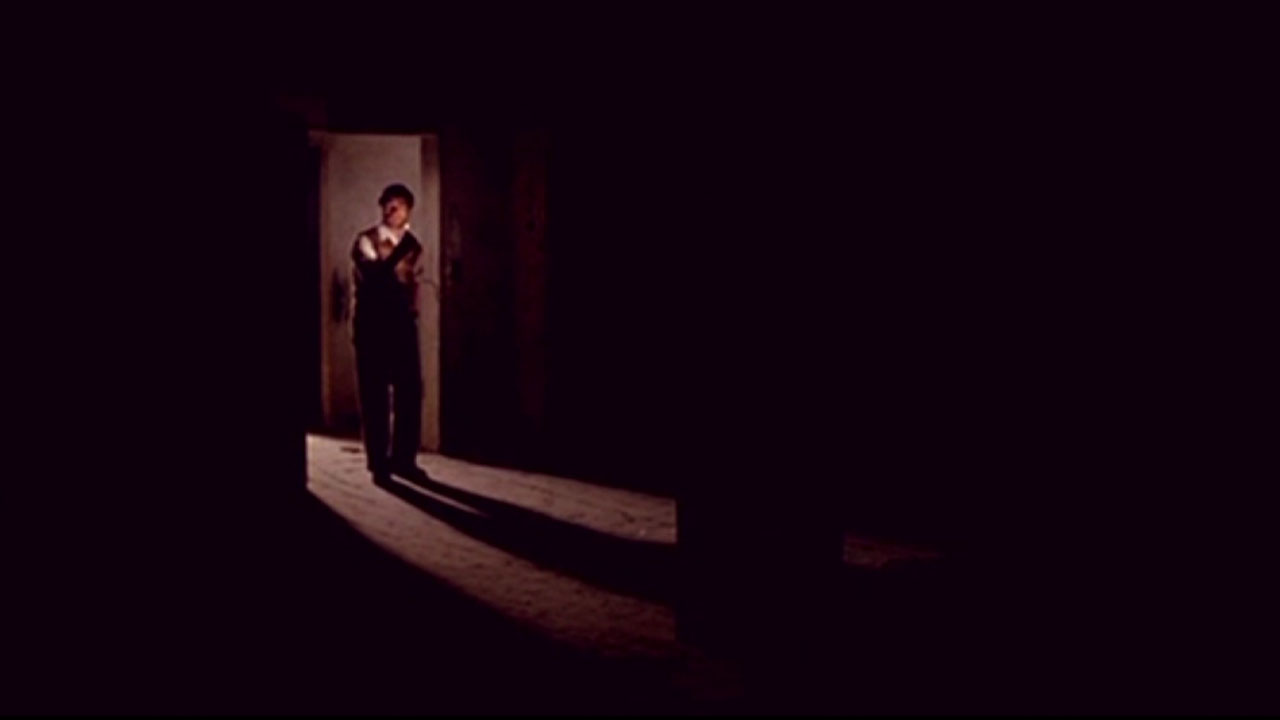

The House With Laughing Windows (1976)

Another giallo set in the sunshine of the Italian countryside, this one tells the story of a young man assigned to restore a fresco in a remote church. Pretty soon the potentially-crazy townsfolk are piling up, while our hero investigates dark attics and listens to an all-time creepy series of voice messages.

Pupi Avati’s film stands as a classic in part thanks to its completely unhinged ending, a genre-best descent into madness.

The Strange Colour of Your Body’s Tears (2013)

Directing pair Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani have turned giallo signifiers into their stock in trade—their three films (also including Amer and Let the Corpses Tan) place full focus on the sensory experience: leather creaks, eyes widen, edits quicken, and plot takes a back seat. It’s like they’ve absorbed the genre into their bones and replicated its essence on screen.

The influence of giallo permeated cinema a long time ago, and filmmakers like Cattlet, Forzani, and Edgar Wright will draw influence from it for a while yet. In turn, new audiences will dig into the back catalogue of this very distinct type of movie, and discover all its perversion and stylistic excesses for themselves.