The underrated Samaritan begs the question: where are all the working class superheroes?

Where have all the good men gone, and where are all the blue-collar gods? Despite its weak reviews, Samaritan moved Luke Buckmaster with its down-to-earth message of humble heroism.

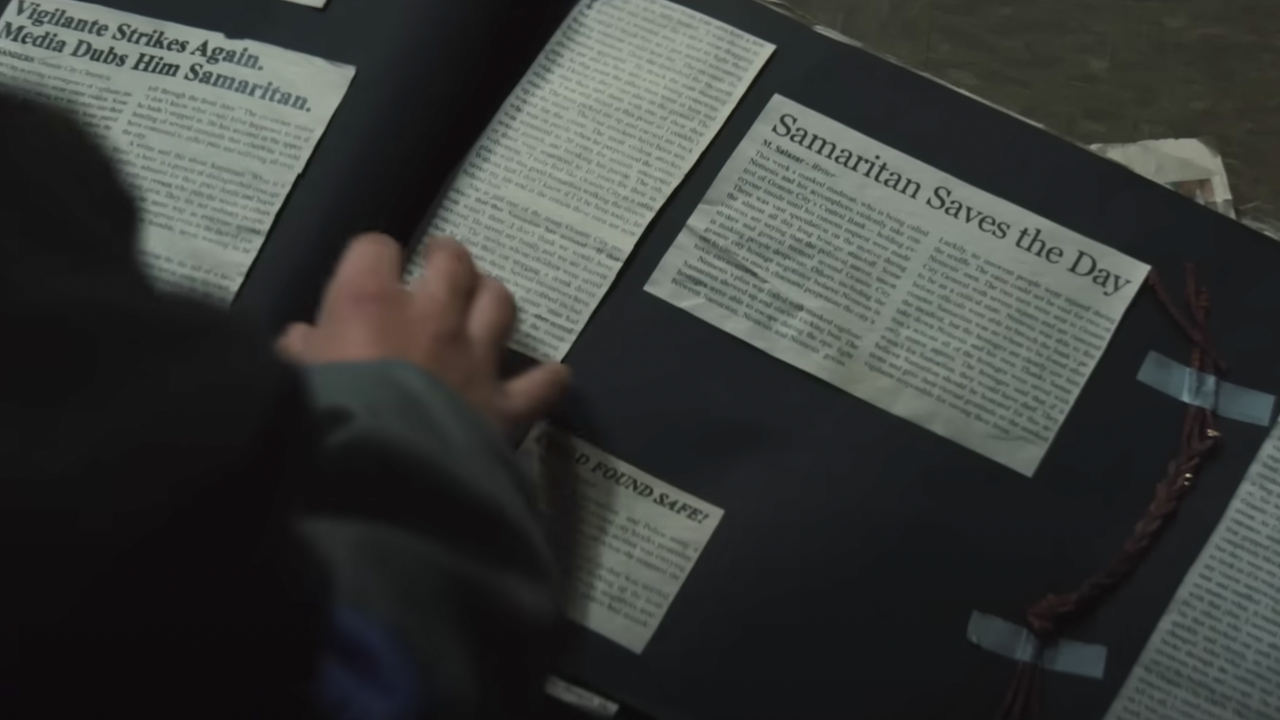

There are good reasons why critics have sunk the boot into Sylvester Stallone’s new movie. The writing in Samaritan can be goofy, the action scenes paint-by-numbers, the Tom Hardy-lite villain lame. Sly is Sly: presenting as a banged-up bloke who recently drank too much, or had a stroke, or possibly both. Opening with a child delivering a monologue about a local legend—a superhero named Samaritan and his arch enemy Nemesis, both believed to be dead—it’s unclear whether the film has been intentionally styled from a kiddish perspective, or whether it’s just a bit stupid.

Probably the latter, but it isn’t the lemon some have proclaimed. In fact a couple of key features carved out by Australian director Julius Avery make it an interesting addition to the superhero cannon, distinguishable in a bloated genre stuffed with same-old same-old.

The first is a vivid sense of place and community. Samaritan takes place in Skid Row: a lower socioeconomic section of the city synonymous with things that are torn and broken. It’s the kind of place where the weather always seems bad; two of Stallone’s earliest scenes, in fact, take place in the rain. Thirteen-year-old protagonist Sam (Javon Walton) is spray-painting a dumpster when he first catches a glimpse of Stallone’s hoodie-wearing garbage man Joe, retrieving something from the bin. We learn he collects and repairs busted radios.

The population share intergenerational destitution and a crippling sense of hopelessness, aesthetically reiterated through cement-like greys and industrial tones. A TV news bulletin reports that unemployment is on the rise, homelessness is at an all-time high, and the rate of evictions is unprecedented.

Sam’s belief that Joe is the legendary Samaritan, alive and well but keeping a low profile, is supported when Joe comes to his rescue, saving him from goons using superhuman abilities. The emergence of Stallone the superhero, from the fog and drizzle of this pinched community, raises the broader question of why there are so few working class superheroes in movies. How many can you name who tough it out in a crappy job for a shitty pay, living in a neighbourhood filled with struggling people?

The sheer wealth of the superhero collective extends much further than characters—such as Iron Man and Batman—whose prosperity is narratively acknowledged. The entire MCU collective for instance reeks of affluence, from Doctor Strange (an ex-surgeon) to Black Panther (a king-like ruler) and that family of green things: Bruce Banner (a physicist) and Jennifer Walters (an attorney).

Most depictions of Peter Parker (aka Spider-Man) and Clark Kent aka (Superman) have them working humble-ish jobs: a newspaper photographer and journalist respectively. But these guys aren’t doing it tough, rather strategically using their professions to place them in the thick of the action. Movie superheroes who aren’t affluent in origin tend to be subsumed into affluence, joining the ultra elite and never looking back.

Why? Because to be a valuable member of society is to be wealthy, and to be wealthy is to be valuable. This is the fiction we are told again and again to justify the grotesqueries of neoliberalism, which accelerates the gap between rich and poor and insists that competition is the only legit organising principle for human activity.

Our world society elevates the ultra rich to the status of demigods; people such as Elon Musk or Donald Trump are frequently discussed in the context of saviours and villains. The dream of the poor is to be wealthy. The dream of the wealthy is to mould the world in their image.

We have reached a point in history where nobody really believes the wheels of capitalism will stop turning in the western world, unless triggered by the collapse of society itself. As scholar Fredric Jameson wrote in New Left Review: “someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.”

Informed by the rise of fascism, the distorted values espoused by superhero movies are also so entrenched that audiences can barely imagine these stories told any other way. Time and again narratives involve entrusting our future to a privileged few, in the hope they will save us from existential crises: a particularly dangerous belief in the era of rapidly accelerating climate crisis and extreme political partisanship. Netflix’s magnificent 2019 series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance presents a reminder that it doesn’t have to be this way, with its rich messages about collectivism and working together.

And now there’s Samaritan, which taps into an idea so comprehensively rejected it’s become inspirational in and of itself: that even the poor, god forbid, can be superheroes. And that being one does not automatically entail an egocentric view of the self.

Down-in-the-mouth old Joe, just a humble garbo from the Bronx, will not have his portrait hung in a hallway of great superheroes any time soon. But this man who wears hoodies and walks around in the rain dares to suggest there’s merit in being modest and humble; in finding virtue not by exercising his powers but resisting them.

The Spider-Man movies love to regurgitate Uncle Ben’s pseudo-philosophical babble about great power and great responsibility. Maybe Peter Parker should sit down for a cuppa with Joe: here’s a guy who talks the talk and walks the walk.